Journal of caring sciences. 12(2):129-135.

doi: 10.34172/jcs.2023.30679

Original Article

A Mobile Application to Assist Alzheimer’s Caregivers During COVID-19 Pandemic: Development and Evaluation

Parastoo Amiri Resources, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Maryam Gholipour Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Sadrieh Hajesmaeel-Gohari Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 2, *

Kambiz Bahaadinbeigy Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 3

Author information:

1Student Research Committee, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

2Medical Informatics Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

3Digital Health Team, The Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Abstract

Introduction:

Access to healthcare services for patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was limited during the COVID-19 pandemic. A mobile application (app) can help overcome this limitation for patients and caregivers. Our study aims to develop and evaluate an app to help caregivers of patients with AD during COVID-19.

Methods:

The study was performed in three steps. First, a questionnaire of features required for the app design was prepared based on the interviews with caregivers of AD patients and neurologists. Then, questionnaire was provided to neurologists, medical informatics, and health information management specialists to identify the final features. Second, the app was designed using the information obtained from the previous phase. Third, the quality of the app and the level of user satisfaction were evaluated using the mobile app rating scale (MARS) and the questionnaire for user interface satisfaction (QUIS), respectively.

Results:

The number of 41 data elements in four groups (patient’s profile, COVID-19 management and control, AD management and control, and program functions) were identified for designing the app. The quality evaluation of the app based on MARS and user satisfaction evaluation based on QUIS showed the app was good.

Conclusion:

This is the first study that focused on developing and evaluating a mobile app for assisting Alzheimer’s caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. As the app was designed based on users’ needs and covered both information about AD and COVID-19, it can help caregivers perform their tasks more efficiently.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, COVID-19, Caregiver, Mobile application

Copyright and License Information

© 2023 The Author(s).

This work is published by Journal of Caring Sciences as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Dementia is the loss of memory and other mental capabilities, which is severe enough to affect daily activity. It is caused by physical changes in the brain.1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia which is characterized by a gradual decrease in mental ability and neurological, psychological, and behavioral disorders.2 This chronic disease decreases the quality of life and imposes an economic burden on the family.3 Currently, about 50 million people worldwide live with AD, and about ten million new cases are reported annually. Although age is the strongest risk factor for dementia, and this disease often occurs in people over 60 years, it is not limited to this age and may affect younger people.4 AD is one of the main causes of death globally and is reported to be the sixth cause of death in the world.

AD has significantly impacted the affected person, caregivers, and society.5 Taking care of these people impose huge financial burdens and has many psychological consequences.6-8 Patients with AD depend on caregivers (often family members) to carry out their daily activities. Currently, about 8.9 million family members help these patients as caregivers. The exacerbation of the disease increases the caregivers’ workload and affects their emotional and psychological health.9 Caregivers will spend about 15.3 billion hours caring for people with AD in 2020.6 This number of hours indicates the high workload for caregivers.

The management of chronic diseases such as dementia largely depends on the capability of family members to take on and accomplish the role of care. Nowadays, many efforts have been made to reduce the workload and stress of caregivers.10 Mobile phones play an important role in supporting caregivers to perform their daily care activities by providing up-to-date and accessible information.11 Mobile-based applications (apps) are effective for various healthcare tasks such as monitoring symptoms, tracking treatment progress, and training in chronic diseases.12

Studies showed the impact of mobile apps to assist patients with AD. Providing a reminder system in these apps could enable people with low memory to remember all their tasks, which may help prevent the rapid progression of the disease.13,14 These apps also may help manage destructive behavior and improve cognitive function by continuing social interactions.15,16 Some of these apps can assist in decreasing the stress and anxiety of family caregivers by estimating the probability of wandering using geolocation, monitoring the patient in and around the domestic in real-time, as well as helping care administration and services by healthcare providers.17 Today, the death rate of patients with AD has increased in the world with the event of the COVID-19widespread, perhaps due to limitations in access to healthcare services.18 Mobile phone use could overcome limitations in physical communication and in-person access to healthcare services during this widespread.19

To the best knowledge of the authors, there is no study on the development and evaluation of a mobile-based app to help caregivers of patients with AD, especially during COVID-19. Developing a mobile-based app that provides information about all aspects of AD and COVID-19 can reduce the need for face-to-face visits to access healthcare services and assist caregivers in caring for patients appropriately. Therefore, the current study purposes to develop and evaluate a mobile app to assist caregivers of patients with AD during the COVID-19 widespread.

Materials and Methods

This research was a cross-sectional study with a mixed-method research design performed in three steps: identifying the features needed to design the app, developing the app, and evaluating the app.

Identifying the Features

In this step, a semi-structured interview was conducted. The questions of this interview were designed based on a review of the literature and the opinion of neurologists and medical informatics experts. Four questions were asked from the participants: What characteristics of the patients should be included in the app? What information about COVID-19 management is required? What information about AD management is required? What other features should this app have? Participants were 30 caregivers and eight neurologists. The interviews, which were performed by one of the authors (P.A.), continued to reach data saturation. Each interview that lasted for 40 min was recorded for the analysis. Informed consent was obtained from the participants to record the interviews. The content of the interviews was transcribed and entered into MAXQDA software. MAXQDA software (version 2018) was used for the qualitative content analysis.

Based on the information items obtained from the results of the interviews, a questionnaire consisting of 41 items in four categories (patient profile, seven items; management and control of COVID-19, 11 items; management and control of AD, 14 items; and application functions, nine items) was designed. Each item had three choices: ‘essential’, ‘not essential’, and ‘useful but not essential’. A blank row was used to add critical comments by experts at the end of the structured questionnaire. The content validity of the questionnaire was evaluated by four experts (two health information management and two medical informatics). Cronbach’s alpha was calculated 0.87 for the reliability of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was distributed among four neurologists, three medical informatics specialists, and three health information management specialists to determine the content of the app.

The content validity ratio (CVR) was used to analyze the questionnaire. CVR value was calculated for each item and compared with the Lawshe table value.20 According to this table, each item that obtained the CVR of more than 0.62 was accepted and used in the design of the app.

App Development

In this step, the app was developed based on the gathered data from the previous step. The online app maker named Puzzley (https://puzzley.ir) was used for developing the app. This app maker enables users to create their own Android app without needing programming knowledge, with the least time and cost. Apps that are made with this mobile app maker are not different from other types of apps and can be easily published in app stores.

In this step, the quality of the app was evaluated using the mobile app rating scale (MARS) with the participation of two medical informatics specialists in a day. MARS contains 23 items in four sections for objective quality, including engagement (five items), functionality (four items), aesthetics (three items), information quality (seven items), and a section for subjective quality (four items).21 Each item has been designed based on a five-point scale (1=inadequate, 2=poor, 3=acceptable, 4=good, and 5=excellent). For some items, not applicable choice is provided. The mean score of each section was calculated separately.

The level of user satisfaction was evaluated using the questionnaire for user interface satisfaction (QUIS). After two weeks of use, fifteen caregivers evaluated the app using QUIS in a week. This questionnaire has 27 items in five sections, including the overall reaction (six items), screen (four items), terminology and information (six items), learning (six items), and general app capabilities (five items). Each item in the QUIS has a 10-point score in the range of 0 to 9.22 The mean score of each section and an overall mean of the app were calculated separately. The total mean scores of 0 to 3, 3.1 to 6, and 6.1 to 9 were considered as weak, medium, and good, separately. The validity and reliability of Persian version of QUIS were confirmed in the previous study.23

Results

Identifying the Features

The demographic information of the study participants is presented in Table 1. Eight neurologists and 30 caregivers participated in this study with an age range of 35 to 60 and 30 to 70 years old, respectively. The work experience of the neurologists and caregivers was between 5 and 15 and between 6 and 23 years old. Half of the caregivers did not have an academic degree.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristic of the participants in interview

|

Variable

|

No. (%)

|

|

Neurologist

|

|

| Age (year) |

| 35-45 |

5 (62.5) |

| 46-60 |

3 (37.5) |

| Work experience (year) |

| 5-10 |

6 (75) |

| 11-15 |

2 (25) |

|

Caregiver

|

|

| Age (year) |

| 30-40 |

8 (26.7) |

| 41-50 |

12 (40) |

| 51-60 |

6 (20) |

| 61-70 |

4 (13.3) |

| Level of education |

| High school diploma |

15 (50) |

| Bachelor’s |

10 (33.4) |

| Master’s |

5 (16.6) |

| Work experience as a caregiver (year) |

| 6-15 |

22 (73.3) |

| 16-23 |

8 (26.7) |

The interview results were 41 items in four categories, including “patient profile”, “management and control of COVID-19”, “management and control of Alzheimer’s disease” and “application functions”. All the items were considered necessary because the value of CVR was more than 0.62 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perspective of specialists on the necessity of care-educational information and features

|

Data elements

|

Specialists’ perspective

|

| Patient profile |

| Gender |

0.99 |

| Age |

0.95 |

| BMI |

0.65 |

| Level of education |

0.69 |

| Disease stage |

0.99 |

| Address |

0.99 |

| Caregiver’s relationship with the patient |

0.87 |

| Management and control of COVID-19 |

| Definition of COVID-19 |

0.99 |

| Ways to prevent and deal with COVID-19 |

0.86 |

| Symptoms of COVID-19 |

0.88 |

| Side effects of COVID-19 |

0.80 |

| Early measures in case of COVID-19 |

0.99 |

| Information on COVID-19 vaccines |

0.98 |

| Necessary care after vaccination |

0.98 |

| Strategies to control and reduce stress caused by COVID-19 |

0.97 |

| COVID-19 in patients with AD |

0.93 |

| Transfer of COVID-19 from caregivers to an AD |

0.86 |

| Reliable news websites related to COVID-19 |

0.79 |

| Management and control of AD |

| Introduction to AD |

0.88 |

| Alzheimer's from onset to the end |

0.78 |

| Progression of the disease and the role transformation of the caregiver |

0.89 |

| Recommendations in the early stages of AD |

0.90 |

| Recommendations in the middle stage of AD |

0.89 |

| Recommendations in the final stage of AD |

0.90 |

| Eating and drinking, the early stages of AD |

0.80 |

| Eating and drinking, the end of the disease |

0.96 |

| Behavioral changes |

0.97 |

| Pharmacological safety |

0.85 |

| Home security |

0.86 |

| Other diseases |

0.77 |

| Other care matters |

0.78 |

| Care of caregivers |

0.89 |

| Applications functions |

| Initial diagnosis of the possibility of COVID-19 |

0.90 |

| Identification of COVID-19 specific medical centers |

0.87 |

| Identification of COVID-19 vaccine centers |

0.84 |

| Virtual visit |

0.98 |

| Reminder for when to visit the doctor |

0.99 |

| Reminders for when to take medication |

0.99 |

| Identifying high-risk areas |

0.97 |

| Searching |

0.86 |

| App settings |

0.78 |

App Development

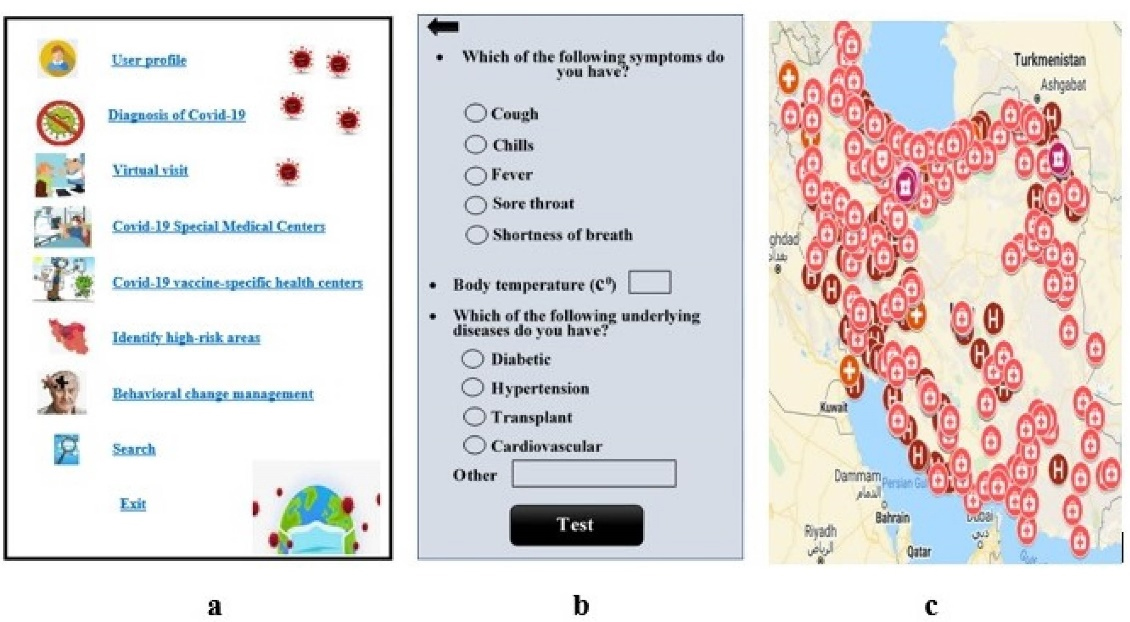

Based on the results obtained from the previous phase, the app was developed (Figure 1). The content of the application was in Persian.The language of the application could be changed to Persian or English in the settings. The app size was 29 MB and can be installed on the Android platform. The demographic information about the patient with Alzheimer’s was entered into the patient profile. Medical information and instructions related to COVID-19 were placed for the management and control of COVID-19 based on WHO resources and expert opinions. The necessary information about Alzheimer’s disease for caregivers was placed in the management and control of AD section based on authoritative academic sources and the “Dard Ashna” website.24

Figure 1.

App pages: a) Home page, b)COVID-19 diagnosis, c) All COVID-19 specialized medical centers in Iran

.

App pages: a) Home page, b)COVID-19 diagnosis, c) All COVID-19 specialized medical centers in Iran

As shown in Figure 1, in the “Diagnosis of COVID-19” section, by entering the symptoms of COVID-19 such as dry cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, body temperature, sore throat, and underlying non-AD, the possibility of COVID-19 disease is determined. In the “Virtual Visit” section, active virtual physicians are listed by entering the type of specialization and location. By clicking on each of their names, the telecommunication hours with them can be informed.

In the section “COVID-19 Special Medical Centers”, users are informed of all active centers to serve COVID-19 patients. In the section “COVID-19 Vaccine Special Health Centers”, all the centers with their exact addresses are displayed by selecting the city.

Due to the rapid spread of this virus, it is better to avoid going to high-risk areas announced by the news. For this reason, in the “Identification of high-risk areas” section, the user is notified of all virus-infected areas by specifying her/his location. Controlling and managing the behavioral changes of patients with AD are among the significant problems for their caregivers. In “the behavioral change management” section, the user can obtain the necessary information to control any behavioral changes.

In the “Searching” section, caregivers can search for more educational information about AD and how to care for this type of patient, as well as COVID-19. In “Settings”, caregivers can control how pages are moved, font type, color, and size of the information.

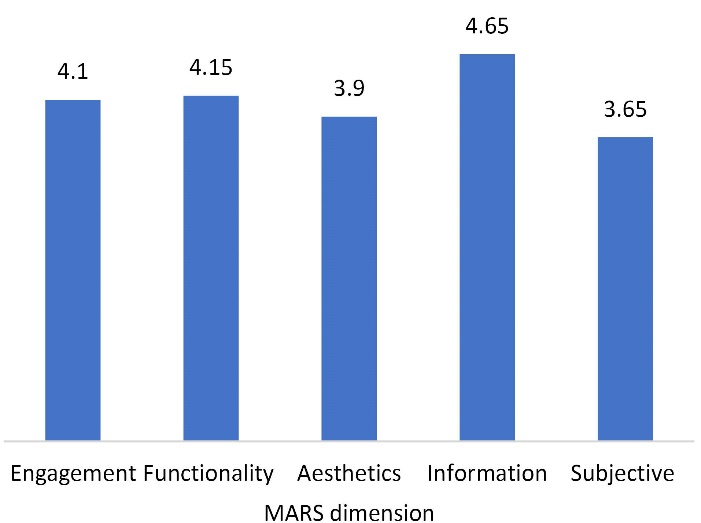

App Evaluation

The quality and user satisfaction of the app were evaluated. The results of the app quality evaluation are shown in Figure 2. In the objective quality section of MARS, the “Information” dimension attained the highest mean score, and the “aesthetic” dimension attained the lowest mean score. The total mean score of the app was 4.09.

Figure 2.

Results of the app evaluation with MARS

.

Results of the app evaluation with MARS

Demographic information of 15 participant caregivers in evaluating user satisfaction is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Participants' demographic information

|

Variable

|

No. (%)

|

| Age (year) |

| 30-50 |

9 (60) |

| 51-70 |

6 (40) |

| Level of education |

| High school diploma |

7 (46.7) |

| Bachelor’s |

5 (16.7) |

| Master’s |

3 (20) |

| Work experience as caregiver (year) |

| 9-15 |

8 (53.3) |

| 16-21 |

7 (46.7) |

Table 4 reveals the average opinions of caregiver’s in assessing the care-educational app. In all the assessed sections, a mean score of more than six was achieved; thus, the participants generally believed that the app was well. The “Screen” section achieved the highest mean score and the “learning” section had the minimum.

Table 4.

Results of the app evaluation with QUIS

|

Questions about each section

|

Mean (SD)

|

| Overall reaction to the app |

| General use of the app |

8.30 (0.11) |

| Ease of use of the app |

8.68 (1.51) |

| How the user feels about using the app |

8.35 (1.23) |

| General design of the app |

8.50 (1.64) |

| Consistent use of the app |

7.78 (0.26) |

| Settings feature of the app |

7.52 (1.30) |

| Total |

8.18 (1.09) |

| Screen |

| Reading characters on the screen |

8.91 (0.80) |

| Using clear statements to simplify tasks |

8.54 (0.16) |

| Organization of information |

7.90 (1.45) |

| Sequence of screens |

8.55 (1.20) |

| Total |

8.47 (0.90) |

| Terminology and information used in the app |

| Use of terms throughout the system |

7.58 (0.25) |

| Task-related terminology |

8.20 (1.30) |

| Position of messages on the screen |

8.68 (1.82) |

| Prompts for input |

7.95 (0.60) |

| App messages to complete user’s tasks |

7.84 (1.70) |

| Error messages |

8.91 (0.82) |

| Total |

8.19 (1.08) |

| Learning |

| Learning to operate the system |

7.96 (1.22) |

| Exploring new features by trial and error |

8.99 (0.55) |

| Remembering names and use of commands |

8.65 (0.21) |

| Straightforward task performance |

7.43 (0.11) |

| Help messages on the screen |

8.25 (1.90) |

| Supplemental reference materials |

7.60 (1.10) |

| Total |

8.15 (0.85) |

| App capabilities |

| App speed |

8.12 (0.71) |

| System reliability |

8.53 (0.25) |

| Number of app specifications |

8.90 (1.40) |

| Correcting user’s mistakes when inputting data |

7.91 (1.13) |

| Designed for all levels of users |

8.26 (0.42) |

| Total |

8.34 (0.78) |

| Total |

8.26 (0.92) |

Discussion

This study focused on developing and evaluating a mobile app for assisting Alzheimer’s caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. This app can be used by the Alzheimer’s patients in the first stage of the disease and all the caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients at every stage. The app was designed in four sections, including “patient profile”, “management and control of COVID-19”, “management and control of AD”, and “application functions.” Among different sections of the objective quality in MARS, the “information” section obtained the highest, and the “aesthetic” section obtained the lowest mean scores. Among different sections of QUIS, the “screen” section achieved the highest mean score, and the “learning” section gained the lowest mean score.

Identifying the Features and App Developing

The app was designed in four sections, including “patient profile,” “management and control of COVID-19”, “management and control of AD”, and “application functions.” Similar to our study, other studies have shown that the information needs of patients with dementia and their caregivers are about characteristics of the disease, disease management, and self-care of caregivers.25However,during the COVID-19pandemic, the needs of caregivers of dementia patients have become broader and have been included protecting the patients from COVID-19 infection, managing the patients if they were infected, managing the changes in the daily activities of patients, managing comorbidities, diet management, and managing behavioral changes.26

On the other hand, the content review of the mobile apps for dementia showed that most of the apps were educational to increase awareness about dementia. Additionally, these apps presented practical caregiving information to increase the quality of life and support caregivers.27 Another study demonstrated that the apps designed for AD mainly have information about caregiving and disease management. Only a few apps offer prevention, early detection, disease monitoring, financial and legal issues, and organization promotion.28 Apps designed only for AD caregivers have features that mainly include tracking patients, daily task management, and monitoring patients and their surrounding environment. Besides, some apps provide mental support for caregivers, educational information, and a platform for communication of caregivers with each other.29

We used the online app maker named Puzzley for developing the app. Other studies used different programming languages to design the mobile health apps.30,31 However, Puzzley enables users to create their Android app quickly without programming knowledge.

App Evaluation

The results of app evaluation using MARS showed that the app had higher quality in terms of information and lower quality in terms of aesthetics. Compared to our study, other studies that have reviewed and evaluated the quality of apps in dementia27 and AD28 using MARS have revealed that apps have higher quality in functionality and lower quality in engagement. These differences may be because the two mentioned studies have evaluated several apps, while our study evaluated only a designed app. The information used in the app that we designed was gathered from standard and reliable resources and proved by Alzheimer’s specialists.24 Since we tried to consider the users’ needs in designing the app, the engagement section could gain an acceptable mean score compared to other studies. Aesthetic criteria include graphics, layout, and visual appeal. Our app could not get a high mean score in terms of aesthetics. Since aesthetics is one of the factors in the acceptability and continuity use of a mobile app,32 it should be considered and improved for this app.

The results of app evaluation using QUIS showed that users had the highest satisfaction with the screen and the lowest satisfaction with the learning capabilities of the app. Similar to this study, a work that evaluated a self-care app for multiple sclerosis with QUIS showed that the “screen” and “learning” sections achieved the highest and lowest mean scores, respectively.30 As a usability principle, information required to use the app should be noticeable and accessible when needed, and users should not have to remember information for using different parts of the app. Moreover, the help section should be provided in an app design to support users in completing their tasks efficiently.33 Since these principles affect users’ satisfaction in using the app, they should be considered in the app design. Moreover, the use of some principles, such as Myer’s multimedia principles that focus on several points in designing educational multimedia, can affect more involvement and improve learning.34

This study has a limitation. The app development was performed only on the Android operating system. The Android operating system has covered most of the mobile operating system’s market.35 Nevertheless, to be more popular, it would be better to develop the app on iOS as well.

Conclusion

To the best knowledge of the authors, this study was the first one that focused on the development and evaluation of a mobile app for assisting Alzheimer’s caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since this app was designed based on user’s needs and covered both information about Alzheimer’s and COVID-19, it can be helpful for caregivers in terms of doing their tasks more efficiently. The evaluation results of the designed app also showed that this app was at a good level in terms of quality and user satisfaction.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the experts and caregivers that helped us and contributed to this study.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Parastoo Amiri, Sadrieh Hajesmaeel-Gohari, Kambiz Bahaadinbeigy.

Data curation: Parastoo Amiri, Sadrieh Hajesmaeel-Gohari, Maryam Gholipour.

Formal analysis: Parastoo Amiri, Sadrieh Hajesmaeel-Gohari, Maryam Gholipour.

Funding acquisition: Sadrieh Hajesmaeel-Gohari.

Investigation: Parastoo Amiri, Maryam Gholipour.

Methodology: Parastoo Amiri, Sadrieh Hajesmaeel-Gohari, Maryam Gholipour.

Project administration: Sadrieh Hajesmaeel-Gohari, Kambiz Bahaadinbeigy.

Resources: Parastoo Amiri.

Software: Parastoo Amiri.

Supervision: Sadrieh Hajesmaeel-Gohari, Kambiz Bahaadinbeigy.

Validation: Parastoo Amiri, Sadrieh Hajesmaeel-Gohari.

Visualization: Parastoo Amiri, Maryam Gholipour.

Writing–original draft: Parastoo Amiri, Sadrieh Hajesmaeel-Gohari, Maryam Gholipour.

Writing–review & editing: Parastoo Amiri, Sadrieh Hajesmaeel-Gohari, Maryam Gholipour, Kambiz Bahaadinbeigy.

COI-statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Ethical Approval

The Ethics Committee of Kerman University of Medical Sciences approved this research with ethical code IR.KMU.REC.1400.381.

Funding

This study was funded by the Kerman University of Medical Sciences with research ID 400000546.

Research Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

-

AD is the common dementia disease.

-

Access to healthcare services for patients with AD was limited during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

Developing a mobile application (app) can help overcome this limitation for the patients and caregivers.

What is new here?

References

- Bliss RM, Wood M. Food discoveries for brain fitness. Agric Res 2010; 58(6):18-21. [ Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, Koumaras B, Chen M, Mirski D. Effects of rivastigmine treatment on the neuropsychiatric and behavioral disturbances of nursing home residents with moderate to severe probable Alzheimer’s disease: a 26-week, multicenter, open-label study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2005; 3(3):137-48. doi: 10.1016/s1543-5946(05)80020-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rice DP, Fox PJ, Max W, Webber PA, Lindeman DA, Hauck WW. The economic burden of Alzheimer’s disease care. Health Aff (Millwood) 1993; 12(2):164-76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.12.2.164 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Dementia. United States: WHO; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia. Accessed December 20, 2022.

- Qiu C, Kivipelto M, von Strauss E. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: occurrence, determinants, and strategies toward intervention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2009; 11(2):111-28. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/cqiu [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mecca AP, van Dyck CH. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s association. Alzheimers Dement 2021; 17(2):316-7. doi: 10.1002/alz.12190 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dillehay RC, Sandys MR. Caregivers for Alzheimer’s patients: what we are learning from research. Int J Aging Hum Dev 1990; 30(4):263-85. doi: 10.2190/2p3j-a9ah-hhf4-00rg [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhu CW, Ornstein KA, Cosentino S, Gu Y, Andrews H, Stern Y. Medicaid contributes substantial costs to dementia care in an ethnically diverse community. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2020; 75(7):1527-37. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz108 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sansoni J, Anderson KH, Varona LM, Varela G. Caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients and factors influencing institutionalization of loved ones: some considerations on existing literature. Ann Ig 2013; 25(3):235-46. doi: 10.7416/ai.2013.1926 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hepburn KW, Tornatore J, Center B, Ostwald SW. Dementia family caregiver training: affecting beliefs about caregiving and caregiver outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49(4):450-7. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49090.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gupta G, Gupta A, Jaiswal V, Ansari MD. A review and analysis of mobile health applications for Alzheimer patients and caregivers. In: 2018 Fifth International Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Grid Computing (PDGC). Solan, India: IEEE; 2018. p. 171-5. 10.1109/pdgc.2018.8745995

- Guo Y, Yang F, Hu F, Li W, Ruggiano N, Lee HY. Existing mobile phone apps for self-care management of people with Alzheimer disease and related dementias: systematic analysis. JMIR Aging 2020; 3(1):e15290. doi: 10.2196/15290 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Soh Y. A cooking assistance system for patients with Alzheimers disease using reinforcement learning. Int J Inf Technol 2017; 23(2):1-12. [ Google Scholar]

- Habash ZA, Hussain W, Ishak W, Omar MH. Android-based application to assist doctor with Alzheimer’s patient. In: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computing and Informatics. ICOCI; 2013.

- Désormeaux-Moreau M, Michel CM, Vallières M, Racine M, Poulin-Paquet M, Lacasse D. Mobile apps to support family caregivers of people with Alzheimer disease and related dementias in managing disruptive behaviors: qualitative study with users embedded in a scoping review. JMIR Aging 2021; 4(2):e21808. doi: 10.2196/21808 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Brown EL, Ruggiano N, Li J, Clarke PJ, Kay ES, Hristidis V. Smartphone-based health technologies for dementia care: opportunities, challenges, and current practices. J Appl Gerontol 2019; 38(1):73-91. doi: 10.1177/0733464817723088 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Moreira H, Oliveira R, Flores N. STAlz: remotely supporting the diagnosis, tracking and rehabilitation of patients with Alzheimer’s. In: 2013 IEEE 15th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom 2013). Lisbon, Portugal: IEEE; 2013. 10.1109/HealthCom.2013.6720743

- Murray ML. Access to health services to reduce morbidity and mortality. Int J Childbirth 2019; 8(4):212-5. doi: 10.1891/2156-5287.8.4.212 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Torous J, Keshavan M. COVID-19, mobile health and serious mental illness. Schizophr Res 2020; 218:36-7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.04.013 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol 1975; 28(4):563-75. [ Google Scholar]

- Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, Zelenko O, Tjondronegoro D, Mani M. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015; 3(1):e27. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3422 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chin JP, Diehl VA, Norman KL. Development of an instrument measuring user satisfaction of the human-computer interface. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); 1988. p. 213-8. 10.1145/57167.57203

- Ayatollahi H, Hasannezhad M, Saneei Fard H, Kamkar Haghighi M. Type 1 diabetes self-management: developing a web-based telemedicine application. Health Inf Manag 2016; 45(1):16-26. doi: 10.1177/1833358316639456 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dardashna. 2021. Available from: https://dardashna.ir/. Accessed September 18, 2021.

- Soong A, Au ST, Kyaw BM, Theng YL, Tudor Car L. Information needs and information seeking behaviour of people with dementia and their non-professional caregivers: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 2020; 20(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-1454-y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vaitheswaran S, Lakshminarayanan M, Ramanujam V, Sargunan S, Venkatesan S. Experiences and needs of caregivers of persons with dementia in India during the COVID-19 pandemic-a qualitative study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2020; 28(11):1185-94. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.06.026 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chelberg GR, Neuhaus M, Mothershaw A, Mahoney R, Caffery LJ. Mobile apps for dementia awareness, support, and prevention - review and evaluation. Disabil Rehabil 2022; 44(17):4909-20. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2021.1914755 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Choi SK, Yelton B, Ezeanya VK, Kannaley K, Friedman DB. Review of the content and quality of mobile applications about Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. J Appl Gerontol 2020; 39(6):601-8. doi: 10.1177/0733464818790187 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Baskys A, Law AV, Roosan MR, Li Y, Roosan D. Scoping review: the empowerment of Alzheimer’s disease caregivers with mHealth applications. NPJ Digit Med 2021; 4(1):131. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00506-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mokhberdezfuli M, Ayatollahi H, Naser Moghadasi A. A smartphone-based application for self-management in multiple sclerosis. J Healthc Eng 2021; 2021:6749951. doi: 10.1155/2021/6749951 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ghazisaeedi M, Sheikhtaheri A, Dalvand H, Safari A. Design and evaluation of an applied educational smartphone-based program for caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. J Clin Res Paramed Sci 2015; 4(2): 128-39. [Persian].

- Malik A, Suresh S, Sharma S. Factors influencing consumers’ attitude towards adoption and continuous use of mobile applications: a conceptual model. Procedia Comput Sci 2017; 122:106-13. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2017.11.348 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nielsen J. 10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design. USA: Nielsen Norman Group; 2020. Available from: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ten-usability-heuristics/. Accessed December 20, 2022.

- Mayer RE, Moreno R. A cognitive theory of multimedia learning: implications for design principles. J Educ Psychol 1998; 91(2):358-68. [ Google Scholar]

- Statista. Mobile Operating Systems’ Market Share Worldwide from 1st Quarter 2009 to 4th Quarter 2022. United States: Statista; 2022. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272698/global-market-share-held-by-mobile-operating-systems-since-2009. Accessed December 20, 2022.