Journal of Caring Sciences. 13(2):116-137.

doi: 10.34172/jcs.33152

Review Article

Trust in Medicine: A Scoping Review of the Instruments Designed to Measure Trust in Medical Care Studies

Ehsan Sarbazi Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Homayoun Sadeghi-Bazargani Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, 1

Zahra Sheikhalipour Writing – review & editing, 2

Mostafa Farahbakhsh Writing – review & editing, 3

Alireza Ala Writing – review & editing, 4

Hassan Soleimanpour Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing, 5, *

Author information:

1Road Traffic Injury Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3Research Centre of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

4Emergency and Trauma Care Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

5Medical Philosophy and History Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

This scoping review study was conducted with the aim of identifying dimensions of trust in medical care, common trust subjects, and medical trust correlates among available instruments.

Methods:

We carried out a scoping review of literature through Medline, EMBASE, Scopus, Google Scholar engine, and various information sources of grey literature, to identify eligible studies up to 2023. We merely included psychometric studies in these areas. Non-psychometrics studies were excluded. Two assessors independently and carefully chose papers and abstracted records for qualitative exploration.

Results:

Fifty-two studies (n=37228 participants) were included in the review. The majority of the participants 67 % (24943) were adults (≥18). One-dimensionality trust was found in 36 % (19) of trust in medical care studies, while multidimensionality was identified in 64 % (33) of the studies. Ten categories of trust in medicine correlates or associates were identified. In terms of trust scales subjects, about 71 % (37) of the scales measured trust in healthcare professions, 14 % (7) health care systems, and the rest were about emergency department, trauma care emergency department, health care team, technology, authorities, telemedicine, insurer, COVID-19 prevention policies, performance, and general trust.

Conclusion:

Various tools have been developed and validated in the field of trust in healthcare, and several domains have been identified. Trust in medicine is correlated by a variety of factors such as patient characteristics, healthcare provider factors, healthcare organization features, health conditions, and social influences. It is suggested that researchers pay more attention to the most commonly known dimensions in preparing tools.

Keywords: Surveys and questionnaires, Mistrust, Distrust, Review, Epidemiology

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Author(s).

This work is published by Journal of Caring Sciences as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Funding Statement

Not applicable.

Introduction

The concept of patient trust has been defined as the idealized acceptance of a vulnerable situation in which the patient entrusts the healthcare professions with the provision of care that aligns with their best interests.1 Patients need to develop trust in their medical professionals when confronted with an illness, regardless of any prior relationship,2particularly when confronting a serious disease in an emergency, they ought to believe their physicians’ care to save their lives.3

The subject of trust in the patient-physician relationship has been explored in various studies.4,5 Trust serves as a determining factor in healthcare utilization,6 hospital performance,7 willingness to treatment adherence,8 enhanced treatment experience, improved information exchange, diminished fear, and reduced instances of seeking second opinions9 and quality of health care. There is growing information that indicates that trust with an unrevealed mechanism (like a placebo) modifies the interaction between the body and mind and thus changes the effectiveness of almost all care procedures in clinical practice.10

The topic of trust within the healthcare practice has received significant attention in current policy discussions. This is largely due to assertions that various factors have contributed to a decline in public trust in healthcare institutions and professionals.11 The development of trust is a gradual progression, characterized by its potential to either advance or diminish in potency as a function of time, demonstrating the properties of the concept.7 It is not possible to demand trust from others,12as it must be acquired through meritorious actions and behavior.

A previous systematic review of the literature study by Ozawa and Sripad resulted in the development of a specialized health systems trust content area framework.13 It was observed that several dimensions, including honesty, communication, confidence, and competence were frequently reflected in the framework measures. On the other hand, concepts like fidelity, system trust, confidentiality, and fairness were found to be of lesser significance in the framework.13

The domains and determinants of trust in healthcare practice in developing countries are possible to be culturally exclusive. An investigation in India indicated that the concepts of “crowdedness” and capacity to meet financial obligations, as well as emotional dimension have elicited considerable attention in medical trust.14

Within the current literature, there is a shortage of international comparative investigations using psychometrically sound tools in these concepts. As the caring systems and cultures are diverse in countries, differences between countries regarding trust in healthcare practice are predictable. However, differences in health-service organizations may also provide reasons for differences between patients’ perceptions of care elements15 such as trust in healthcare professions. The measurement of trust with a valid and reliable instrument is essential,16 but it is a difficult construct to measure.17

To the best of our knowledge, most scales developed to measure trust (in healthcare) have emerged from developed countries. Because of its vital importance to medical practice, we need to obtain a thorough understanding of the nature, knowledge gaps, scope of a body of literature, predictors, and consequences of trust between patients and their health providers.18

Effective assessments of medical trust will be vital resources for evaluating, guiding, and supporting efforts to understand and enhance trust. Also, there is no general agreement about how to best assess trust in medicine. Therefore, characterizing existing measures of medical trust, as well as identifying dimensions to guide future measure creation is needed. This scoping review study was conducted with the aim of identifying dimensions of trust in medicine, trust subjects and correlates among available instruments.

Materials and Methods

Registration and Protocol

This scoping review was prepared in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)19 and recorded at the Pazhoohan Investigation Information System (registration code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.1098).

Data Sources

We searched Medline (via PubMed), Scopus, Embase, Google Scholar, and other information sources of grey literature using the following topic headings and keywords: “Trust” “Medicine,” “Medical,” “Physician,” “Nurses,” “Health Personnel,” “Health Care Professional,” “Healthcare Provider,” “Surveys and Questionnaires,” “Questionnaire,” “Tool,” and their synonyms and related terms. We developed a search strategy in a Supplementary file. In addition, we manually explored the Journal of Trust Research, as well as the bibliographies of all retrieved reports. Also, the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) was searched to identify ongoing systematic reviews on the same topic. The references of eligible papers were manually explored for additional studies that had not been identified through the electronic search. We ran our initial search strategy in March 2023 and updated it in April 2023 by two researchers, namely ES and HS.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria, and Types of Studies

Only psychometric studies with the primary objective of developing or adapting a measurement tool for trust in medical care were considered. Publications were included without time limitations with available titles, abstracts, and full-texts. We considered only English and Persian languages.

Selection Process and Data Extraction

Two assessors screened all titles and abstracts of retrieved papers separately. Additionally, full-texts of related papers were screened for eligibility by two reviewers and the reasons for exclusion were recorded for the excluded full-texts and disagreements were discussed and resolved. The following data was extracted from the papers: the first author, publishing year, country, study design, sample size (SS), language, administration, sampling method, response rate, pilot study SS, target population, subject in medical trust, initial/conceptual dimension, number and name of final dimension, number of items, variance of factors, eigenvalue for factors, reliability, validity including (content, face, structural, constructive, predictive, convergent), scoring range, and correlates or associates of trust in medicine. In order to synthesize the included studies the qualitative data approach of content analysis for variables of interest was used. The risk of bias was not evaluated in the included studies. This is usually how scoping studies are typically done.20,21

Results

Study Characteristics

Eligible Studies

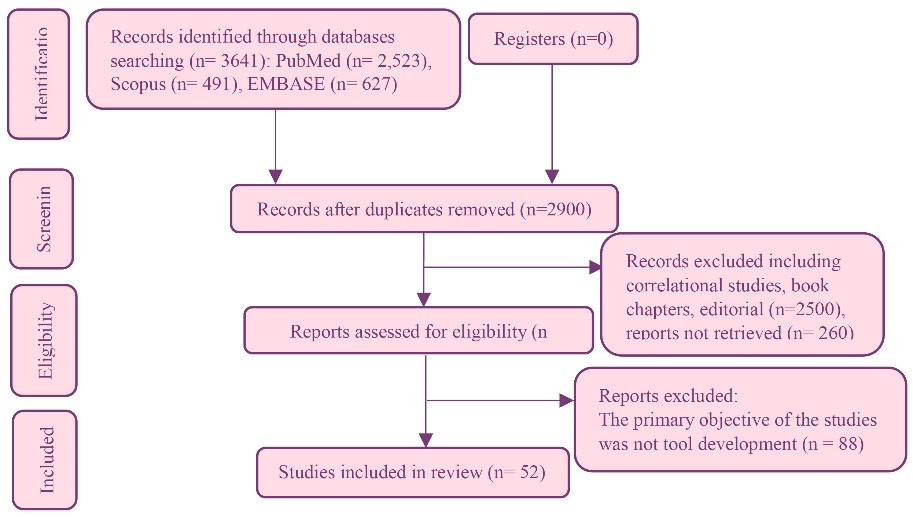

A total of 3641 publications were identified. Out of 3641 studies, 741 of them were duplicates. 400 were selected for further scrutiny on the basis of screening the titles. Following a review of the abstracts, the full text of 140 publications was retrieved, and assessed on their fulfillment of the selection criteria. Finally, 52 publications were synthesized in the current evaluation (Figure 1), of existing evidence between 1990 to 2023 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the trust in medicine scoping review

|

First author/ year

|

Country, Language

|

Design

|

Final dimension(s), Items number in dimension (I), Variance (V), Eigenvalue (λ)

|

Subjects of

trust in medicine

|

Medical trust correlates/Trust in medicine associates

|

| Sarbazi-202322 |

Iran, Persian |

Cross-sectional |

Individual trust: I = 13, v = 43 %, λ = 9.47

system trust: I = 9, v = 5.64 %, λ = 1.24 |

Trust in trauma care in an emergency department |

|

| Richmond-202223 |

USA, English |

Cognitive interviews,

online survey,

Qualtrics Panel |

T-MD*: I = 6, T-DiG and T-HCT: I = 7, communication, competency, fidelity, systems trust, confidentiality, fairness, global trust, stigma-based discrimination |

My doctor, doctors in general, health care team |

Existing trust or mistrust measures, perceived racism in health care, delayed health care seeking, receipt of a routine health exam, and federal government |

| Alaei Kalajahi-202224 |

Iran, Persian |

Online cross-sectional (Telegram, WhatsApp) |

Policy: I = 7, effectiveness: I = 3, equipment: I = 4, prevention: I = 4, participation: I = 2, public education: I = 6, behavior: I = 2 |

Public trust in Covid-19 control and prevention policies |

Not reported |

| Holroyd-202125 |

USA, English |

web-based survey |

Beneficence: I = 8, V = 64 %, λ = 5.41

competence: I = 6, V = 36 %, λ = 3.30 |

Public health authorities |

Trust in the information provided by doctors regarding vaccines, vaccine recommendations, vaccine acceptance, and vaccine |

| Bani-202126 |

Italia, Italian |

Cross-sectional |

Trust in oncologist |

Oncologist |

Satisfaction, trust in the health care system, recommendation, number of consultations, patients' HRQOL, socio-demographics including age, education, and clinical features |

| Comparcini-202027 |

Italia, Italian |

Cross-sectional |

Trust in nurses |

Nurses |

Not reported |

| Ebrahimipour 202010 |

Iran, Persian |

Cross-sectional |

Patient-centered care: I = 6, care policies at the macro level: I = 6, expertise of providers: I = 4, quality of care: I = 9, communication and information presentation: I = 6 quality and cooperation between providers: I = 2 |

Public trust of health care providers |

Not reported |

| Sadeghi-Bazargani-201928 |

Iran, Persian |

Cross-sectional |

Main factor: I = 25, V = 74.1 %, λ = 22.47

specific or optimal task: I = 5, V = 19.2 %, λ = 1.6 |

Public trust in primary health care |

Not reported |

| Abdolahian-201929 |

Iran, Persian |

Cross-sectional |

Professional skill: I = 5 λ = > 1.5, coordination skill: I = 2, λ > 1.5, financial skill: I = 3, λ > 1.5,

(V scale = 73.24 %) |

Patient trust in midwifery care |

Not reported |

| Krajewska-Kułak-201930 |

Poland, Polish |

Cross-sectional |

Trust in nurse |

Nurse |

Not reported |

| Krajewska-Kułak-201831 |

Poland, Polish |

Cross-sectional |

Trust in Physician |

Physician |

+ *: age, education, income, marital status, and number of physician visits

- *: sex and place of residence |

| Kalsingh-201732 |

India, Tamil |

Cross-sectional survey |

Factor 1 (I = 7), factor 2 (I = 2), factor 3 (I = 1), factor 4 (I = 1), (V scale = 59.7 %) |

Physician

(tertiary care hospital), general trust |

+ : General trust |

| Armfield-201733 |

Australia, English |

Telephone survey |

Trust in dentists, V scale = 58.6 %, λ = 6.44 |

Dentists |

Trust in the dentist (last visit, switching), pain, visiting frequency, avoidance, discomfort, gagging, fainting, embarrassment, and personal problems with the dentist. |

| Chatzea-201734 |

Greece, Greek |

Validation study |

Interpersonal trust in teams: I = 6, V = 66.4 %

team performance: I = 4, V = 30.1 % |

Trust

and performance |

Not reported |

| Zhao-201735 |

China, Chinese |

Validation study |

Trust in nurses: λ = 2.356 |

Nurses |

Not reported |

| van Velsen-201636 |

Netherlands, Dutch |

Online survey, survey monkey |

Trust in care (organization: I = 5, treatment: I = 5, professional: I = 4, technology: I = 5, telemedicine service: I = 5) |

Telemedicine |

Not reported |

| Hillen-201618 |

Netherlands, Dutch |

Online e-mail

cross-sectional |

Trust in oncologist

V scale = 82 %, λ = 4.09 |

Oncologist |

Satisfaction |

| Nooripour-201637 |

Iran, Persian |

Cross-sectional |

Trust in nurses: V scale = 61.395 %, λ = 3.070 |

Nurses |

Government nurses are seen as more trustworthy than nurses in other sectors |

| Stolt-201616 |

Finland, Finnish, Swedish, and Greek |

Cross-sectional, cross-cultural, multi-site survey |

Trust in nurses, V scale = 0.67-0.86 % |

Nurses |

Country and previous hospital experiences |

| Tabrizi-201638 |

Iran, Persian |

Cross-sectional |

Patient centeredness, macro-level policies concerning health care, professional expertise of health providers, quality of care, information provision and communication, quality of cooperation between health care providers |

Public trust in health services |

The highest level of trust is typically placed in specialists, pharmacists, and nurses, while the lowest level of trust is observed in macro-level policy. Also, Lower-income individuals tend to have more trust in health services.

+ : older age, education status including doctorate, illiterate, and elementary |

| Gopichandran-201517 |

India, English, Tamil |

Cross-sectional survey |

Competence, assurance of treatment, respect and loyalty |

Physician (PHC) * |

Not reported |

| Aloba-20144 |

Nigeria, English |

Cross-sectional |

Factor 1: V = 28.82 %, λ = 3, factor 2: V = 19.23 %, λ = 2 |

Physician |

Number of admissions, schizophrenic relapses, and adherence |

| Dong-201439 |

China, Chinese

(Mandarin) |

Cross-sectional |

Factor 1: V = 39.54 %, λ = 4.35, factor 2: V = 15.65 %, λ = 1.72 |

Physician |

Satisfaction, recommendation, disputation, seeking a second opinion, adherence, and switching physicians

+ : age and physician visits |

| Peters-201440 |

USA, English |

Cross-sectional |

Trust in physician, V scale = 25 % |

Physician |

-: Previous experience of racism, specifically in healthcare

+ : sense of ethnic identity |

| Hillen-201341 |

Netherlands, English |

Cross-sectional |

Trust in oncologist |

Oncologist |

Satisfaction, recommendation, number of visits, trust in health care |

| Lori-201342 |

Liberia, English, Kpelle, and

Mano |

Cross-sectional |

Trust: I = 7, λ = 2.736, teamwork: I = 4, λ = 1.706 |

Trust and teamwork among maternal healthcare workers |

Not reported |

| Dinc-201243 |

Turkey, Turkish |

Cross sectional |

Trust in health care (providers: λ = 7.30, payers: λ = 2.61, institutions: λ = 1.21), V scale = 65 %, |

Health care systems |

Low education level and low perceived income. |

| Bova-201244 |

USA, English |

Prospective instrument

design |

Health care relationship trust: V scale = 67 %, λ = 9.05 |

Patient–provider trust

in a primary care population |

Race, ethnicity, type of provider e.g. attending physicians are trustful than medical residents, age, length of time with the primary care provider, and mental health |

| Eisenman-201245 |

USA, English |

Survey |

Public health disaster trust: λ = 2.45 |

Public health disaster–related trust |

Racial or ethnic minority, following public health recommendations, public health behavior, and household disaster preparedness |

| Jeschke-201246 |

Germany, German |

Cross-sectional |

Confidence in labor, partner’s support, trust in medical competency, being informed, V scale = 69.6 % |

Delivery |

Pain manageability and partner’s support |

| Hillen-201247 |

Netherlands, Dutch |

Cross sectional |

Trust in oncologist: V scale = 61.51 % |

Oncologist |

Age, mental health, and nationality |

| Thom-201148 |

USA, English |

Prospective |

Patient role: I = 8, λ = 11.5

Respect for boundaries, I = 4, λ = 2.2 |

Physician trust in the patient |

Clinician-reported behaviors |

| Montague-201049 |

USA, English |

Survey

(e-mail data base) |

Trust in technology: λ = 31.17, I = 31, trust in provider: λ = 12.27, I = 26, how the provider uses the technology: (λ = 5.55), I = 22), V scale = 39 % |

Medical technology |

Not reported |

| Radwin-201050 |

USA, English |

Cross-sectional |

Trust in nurses: V scale = 59 %, V = 66 % |

Nurses |

Not reported |

| Zhang-200951 |

Singapore, English |

FGD*, cross-sectional |

Benevolence: I = 6, technical competence: I = 2, global trust: I = 4, V scale = 55 %, |

Pharmacists |

Satisfaction with service, return for care, and preference for medical decision-making pattern |

| Bachinger-200952 |

Netherlands, Dutch |

Cross-sectional |

Trust in physician: V scale = 63.45 % |

Physician |

Age, satisfaction, length of relationship, recommendation, and unwillingness to switch |

| Ngorsuraches-200853 |

Thailand, Thai |

Scale development, testing, and improvement. |

Benevolence, technical, competence, communication, V scale = 55.96 % |

Community pharmacists |

Agreement with a pharmacist, turning for assistance when needed, preferred pharmacist, asking for a pharmacist’s service, and following recommendation |

| Rotenberg-200854 |

UK, English |

Cross-sectional

(two part) |

Honesty: V = 30 %, λ = 2.67, emotional: V = 15 %, λ = 1.36, reliability: V = 12 %, λ = 1.16, V scale = 58 %, |

General physicians |

+ : With adherence to medical regimes both child-reported and parent-reported. |

| Egede-200855 |

USA, English |

web-based survey,

cross-sectional

(two phase) |

Trust in health care (providers: I = 10, λ = 6.29, payers: I = 4, λ = 2.40, institutions: I = 3) λ = 1.30) |

Health care systems |

Patient-centered care, locus of control-chance, medication no adherence, social support, and satisfaction |

| Bova-200656 |

USA, English |

Instrument development study |

Interpersonal connection: I = 5, V = 51 %, λ = 7.6, respectful communication: I = 4, V = 10 %, λ = 1.5, professional partnering: I = 6, V = 8 %, λ = 1.2, V scale = 69 % |

Health care providers |

Possible relationship with depression |

| Kelly-200557 |

UK, English |

development

and prospective phases |

We did not get access to the domains name. V scale = 52 % |

Emergency department |

Not reported |

| Dugan-200558 |

USA, English |

Telephone survey (two phase) |

Trust in a physician, trust in a health insurer, trust in the medical profession |

Physician, health insurer, medical profession |

Satisfaction, care, recommend, no desire to switch, length of care, visits number, choice in the selection, not having a dispute, sought a second opinion, being in managed care.

Poorer physical health, mental health is linked to lower trust in a physician. |

| Freburger-200359 |

Georgia, Georgian |

Longitudinal project part of an ongoing, |

Trust: I = 11, V = 18 %, skepticism: I = 4 |

Physician |

-: Skepticism, independent decision making, older age, minority status, higher education, diagnosis of fibromyalgia or osteoarthritis, and poorer health |

| Hall-200260 |

USA, English |

Cross-sectional |

Trust in primary care providers |

Primary care providers |

Satisfaction, desire to remain with a physician, willingness to recommend to friends, do not seeking second opinions, membership in managed care, choice of physician, no disputes, length of relationship, and number of visits |

| Hall-200261 |

USA, English |

Telephone survey |

Trust in the medical profession: V scale = 78 %, λ = 8.2 |

Medical profession |

Satisfaction with care, general trust, interpersonal trust, following recommendations, no prior disputation, no sought second opinions, and no switching |

| Straten-200262 |

Netherlands, Dutch |

Phased design (qualitative, quantitative) |

Patient focus: V = 32.5, λ = 11.7, policies at macro level: V = 7.6, λ = 2.7, providers’ expertise: V = 5.6, λ = 2, quality of care: V = 4.5, λ = 1.6, Information supply and communication: V = 3.7, λ = 1.3, quality of cooperation: V = 3.3, λ = 1.2, |

Public trust in health care |

Elderly people, lower level of education, experience via media, the experience of parents, the experience of friends, and personal experience are associated to higher public trust in health care systems. |

| Leisen-200163 |

USA, English |

Cross-sectional |

Benevolence, technical competence |

Physician |

Friend referral, compliance with recommendations, return for care, quality of care, satisfaction, time (number of previous service encounters), incentives for opportunistic behavior, believed breadth of choice in primary care physician, awareness of utilization reviews by insurers, awareness of financial incentives |

| Thom-19998 |

USA, English |

Prospective study

(two steps) |

Trust in physician |

Physician |

Satisfaction with care, perceived humaneness of physician behavior, interpersonal trust, continuity, adherence, age, gender, and education |

| Safran-199864 |

USA, English |

Mail survey with limited telephone follow-up |

Trust |

Primary care

physician |

Accessibility (organizational, financial), continuity (longitudinal, visit-based), comprehensiveness (contextual knowledge of patient, preventive counseling), integration, clinical interaction (clinician-patient communication, thoroughness of physical examinations), and interpersonal treatment |

| Kao-199865 |

USA, English |

Cross-sectional survey |

- |

Primary care physician |

Method of payment, overall trust, health plan, health status, graduated place of physician, lower number of physicians in practice, choice, longer relationship, physician behavior |

| Thom and Campbell-199766 |

USA, English |

FGD |

Thoroughly evaluating problems, understanding patient's individual experience, expressing caring, providing appropriate and effective treatment, communicating clearly and completely, building partnership / sharing power, demonstrating honesty / respect for patient, predisposing factors, structural/staffing |

Physician |

Not reported |

| Anderson-199067 |

USA, English |

Cross-sectional

(two study) |

Trust in physician V scale = 38.4 % |

Physician |

Health locus of control, powerful-others, internal locus of control, chance locus of control, and social desirability |

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of this study

.

Flow diagram of this study

Distribution in Countries and Languages

Trust in medical care was the subject of studies in a wide range of countries. Of 52 studies, 19 were done in the United States,8,23,25,40,44,45,48-50,55,56,58,60,61,63-67 seven in Iran,10,22,24,28,29,37,38 six in the Netherlands,18,36,41,47,52,62 two in Italy,26,27 two in Poland,30,31 two in India.17,32 Also, other studies were two in China,35,39 two in the UK,54,57 and the rest (one) in Australia,33 Greece,34 Finland,16 Nigeria,4 Liberia,42 Turkey,43 Germany,46 Singapore,51 Thailand,53 Georgia.59

From 52 studies, 27 of the tools developed on the subject of trust in medicine were in English language, seven in Persian, five in Dutch, three in Greek, two in Italian, two in Polish, two in Tamil, two in Chinese, two in German, and the rest (one) in Finnish, Swedish, Kpelle, Mano, Turkish, Thai.

Study Design, Administration of Tools, Sampling Methods, Response Rate, and Target Population in İnstruments Designed for Trust in Medicine Studies up to 2023

Cross-sectional studies were the most frequent 80 % (n = 42) type of study. Regarding administration of tools, 61 % (n = 32) were self-reported. As to the types of sampling methods, twenty were nonprobability, seventeen were random, three were in a cluster, three in multistage, two were in stratified, and five did not report the sampling methods. In sum, 37228 cases were included in these studies with a minimum sample size of 36 and a maximum of 3442 cases. The mean response rate was 64 ( ± 22.8). Sixty-seven percent (n = 35) of the studies have used pilot study. The majority of the participants 67 % (n = 24 943) were adults ( ≥ 18). Also, 47 % (n = 24) included diverse patients like cancer, internal medicine, general surgery, obstetrics gynecology, diabetes, chronic health conditions, rehabilitation, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, psychiatric disorders, HIV, emergency patients, family practice, traumatic patient (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies included in scoping review

First author/

year

|

Translation

|

Administration

|

Sampling method, Sample size, (Response rate), [Sample size in Pilot study]

|

Target

population

|

Initial or conceptual dimension

|

Initial

(final) item

|

Reliability

(α)

|

Validity

(Content (C) & Face (F), language)

|

Validity

([structural], constructive, predictive, convergent )

|

Scoring

(Score range)

|

Item generation sources

|

| Sarbazi- 202322 |

r |

Self-report |

Convenience, 498, [20] |

Traumatic patients |

- |

65 (22) |

0.95 |

C:relevancy, necessity, clarity, redundant, appropriates |

[EFA, Oblimin rotation, scree plot] |

Likert (5) SDA*; SA*

[22-110] |

PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Web of Knowledge, Magiran, Google scholar, expert, patients |

Richmond-

2022 23 |

r

Adapt |

Interview,

Self-report |

Convenience

(flyers posted public libraries and Facebook), 801, [21] |

≥ 18, U.S. adults |

Competence, fidelity, honesty, confidentiality, confidence, communication, systems trust, fairness, global trust |

45,60,

MD (2),

DiG

&

HCT(29) |

0.90 |

C: clarity, conciseness, relevance

PF |

[EFA, CFA (oblique Promax),

scree plot],

Ppredictive validity |

Likert (5) SDA; SA

[NR] |

13Ô

|

| Alaei Kalajahi- 202224 |

r |

Self-report |

Convenience random, 805 |

General people |

- |

41(29) |

0.95 |

C: transparency

relevance, simplicity, necessity

CVR* = 0.73, CVI* = 0.89

based on experts’ opinions |

[EFA, CFA (Varimax)] |

Likert (5) SDA = 1;

SA = 5

[28-140] |

Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science |

| Holroyd- 202125 |

r |

Telephone Interview (pretest)

, Self-report |

Convenience

(in pretest), 1925, [20] |

≥ 18 |

Beneficence, efficiency, innovation, objectivity, competence, equity, transparency, responsiveness, accuracy, integrity |

20

(14) |

0.86 |

C:

clarity, completeness (research team) |

[CFA PCA, (oblique Promax),

EFA, scree plot] |

Likert (4) SA; SDA

[14-56] |

Trust in

government literature using 68,69 |

| Bani-202126 |

P* |

Self- report (research assist) |

NR, 194, (84 %),[5] |

> 18, cancer patients in oncology dep |

- |

(18) |

0.95,

SF#

(0.88) |

Comprehensibility |

[CFA],

Pconstruct validity using correlation |

Likert (5) SDA = 1; SA = 5

[1–5] |

41,47

|

| Comparcini- 2020 27 |

P |

Self-report |

Convenience, 200,

(98 %), [30] |

18–75,

patients |

- |

(4,5) |

4:0.83

5:0.79

correlation : 0.59-0.67 |

C: clarity, relevance,

language validity: semantic, equivalence |

[CFA] |

Likert (6) never = 1; always = 6

[1-10] |

70

|

| Ebrahimi Pour-2020 10 |

P |

Self-report |

Random cluster, 50 |

Patients of government hospitals. |

- |

36

(33) |

0.83,

ICC* = 0.81 |

C:

comprehensibility, clarity,

simplicity and communication

CVR, CVI = 0.83 |

- |

Likert (5) very low = 1;

very high = 5

[0-100] |

62

|

| Sadeghi-Bazargani- 2019 28 |

No |

Interview |

Two stage cluster, PPS, 600 |

≥ 15, head

of the households or housewife |

- |

42

(30) |

0.98

ICC = 0.94

R* = 0.89

Kendall’s tau-a &b = 0.77 |

C: grammar, order of words, using correct and appropriate words scoring, necessity, relevance, clarity), m kappa = 0.94

Experts, |

[EFA using PFA

(Varimax)] |

Likert (5), very low = 0;

very high = 4

[0-120] |

0000000000000000000000000000000000000PubMed,

Science Direct, Scopus, Web of Knowledge |

| Abdolahian- 2019 29 |

P |

Self-report |

Consecutive, 210, [10] |

15-57, childbearing age female |

- |

10 |

0.81

ICC > 0.81 (one month) |

C: Difficulty, relevancy, vagueness, ambiguity, grammatical, word choice, CVI(clarity, simplicity, elatedness), CVR(necessity), midwifery professors |

EFA, CFA, (Varimax) |

Likert (5),

at all = 1; totally = 5

[10-50] |

65

|

| Krajewska-Kułak-2019 30 |

NR |

Self-report |

Random, 1200, [130] |

Surgical and medical wards |

- |

- |

> 0.70 |

C: understanding

the statements, changes in item wording (doctor, nurse) |

Using correlation |

Likert (5), SDA = 1; SA = 5

[11-55] |

67

|

| Krajewska-Kułak-2018 31 |

P, Adopt |

Self-report |

NR, 849,

(94.3 %) |

Hospitals, dep. of internal medicine |

- |

11 |

0.89,

R: 0.94-0.95 |

C: degree of difficulty of wording |

Using association |

Likert (5),

SA- SDA

[NR] |

67

|

| Kalsingh- 2017 32 |

P |

Interview |

Convenience, 288, (92.9 %) |

≥ 18, patient of internal medicine,

general surgery, obstetrics gynecology outpatient |

Physician dependability,

knowledge and skills, confidentiality, reliability

of information |

Physician (11),

General (30) |

0.707,

R:0.14-0.50 |

PF

PC

Pvalidity of translation |

[EFA] |

Likert (5), SDA = 1;

SA = 5

[(11-55), General (30-150)] |

67

|

| Armfield- 2017 33 |

r |

Self-completing |

Simple random, national, 596,

(41.1 %) |

≥ 18 |

Fidelity, conflict of interest, competence, honesty, global trust |

11 |

0.92,

R:

0.41-0.84,

ICC = 0.52 |

C: modifications the term ‘physicians’ to ‘dentists’, as well as some minimal

wording changes |

[EFA, PAF], Pconvergent validity |

Likert (5) SDA = 1;

SA = 5

[11-55] |

61

& researcher |

| Chatzea-2017 34 |

P,

Cultural

adapt |

Self-report |

Randomization, 36,

(100 %),[8] |

Nurses, physicians, porters, university hospital (surgery anesthesiology) |

Facotor1: tasks, expertise, help, sources, ideas and

suggestions,

factor 2: effective completion of tasks, problem management, quality of work and critical mistakes |

10 |

0.97,

ICC = 1 |

C:

linguistic or

comprehensiveness problems |

[EFA principal (Varimax)],

PReproducibility & construct validity using R |

Likert (5),

SDA = 1; SA = 5

[10-50] |

71

|

| Zhao-2017 35 |

P,

Adopt |

Self-report |

NR,190, [10] |

≥ 18, hospitalized patients with cancer |

Assurance to knowledge and technique, consistency, respect, reassurance, trust to future |

41

(4) |

0.817,

retest (R = 0.866), R split-half = 0.74, |

Readability and feasibility |

[EFA, CFA] Pconcurrent validity |

Likert (5),1 never = 1; always = 5

[4-20] |

72

|

| van Velsen-2016 36 |

r |

Self-report |

Convenience random

) two organizations patients web link), 795, (20.2 %),[7] |

Patient with rehabilitation (anticoagulation),

mean age 68 ( ± 11) |

Trust in: care organization, care professional, treatment, technology, telemedicine, trusting intention, trust-related behavior |

25

(24) |

0.91 |

C:

clarity and legibility patient, easier to read and interpretation |

Pconvergent validity using R |

Likert (5),

Disagree = 1; agree = 5

[24-120] |

patient FGD & 73-75 |

| Hillen-2016 18 |

r |

Self-report |

Random (148 panel members), 92,

(68 %) |

Adult cancer patients |

Competence, honesty, fidelity, caring, overall trust |

5 |

0.94

R = 0.77-0.94 |

F |

[EFA, (Varimax)],

PConvergent validity |

Likert (5), SDA = 1; SA = 5

[1 to 5] |

41,47

|

| Nooripour- 2016 37 |

P |

Self-report |

Quota random, 90 |

(18-50),

Inpatients in hospitals |

- |

5 |

0.84 |

PF(expert) |

[EFA, scree plot] |

Likert (6), never = 1; always = 6

[5-30] |

50

|

| Stolt-2016 16 |

P |

Self-report |

Multistage Sampling, 599,

(52-88 %)

, [104] |

≥ 18,

in-patient cancer,

four European countries |

- |

4 |

0.84-0.95, R:100 % |

C: semantic equivalence (patient interviews and expert panel) |

[EFA, PCA (Promax)] |

Likert (5), never = 1;

always = 5

[4-20] |

Patient

interviews &

50,76 |

| Tabrizi-2016 38 |

P |

Face-to-face interviews |

Random cluster, 1050, [30] |

(15–88), head of household |

- |

25 |

0.86 |

C: expert opinion

CVR = 0.81 |

NR |

Likert (4) |

77

|

| Gopichandran- 2015 17 |

P |

Interview

(researcher administered) |

Multistage technique, 616, [10] |

≥ 18,

developing country setting |

Perceived competence, assurance of treatment irrespective of ability to pay or at any time of the day, patients’ willingness to accept drawbacks in health care, loyalty to the physician and respect for the physician |

31,22

(12) |

0.92

R > 0.4 only 22 items |

PF (experts),

PTranslation validity, |

[CFA]

PItem response analyses |

Likert (5), SA- SDA

[(-2, + 2)

-44 - + 44] |

14

|

| Aloba-2014 4 |

r |

Interview |

Consecutive, 223 |

≥ 18, outpatients psychiatric disorders university hospital |

- |

11 |

0.68 |

- |

[PFA (Varimax)], correlation |

Likert (5),

SDA = 1; SA = 5

[0-100] |

8,67

|

| Dong-2014 39 |

P |

Self-report |

Random, 3442,

[10] |

≥ 18, outpatients at general hospitals |

- |

11 |

0.83 |

C: cultural relevance, equivalence (by panel), cognitive debriefing by patients), clarity, interpretation,

Semantic: (conceptual, idiomatic consistency) |

[EFA,

direct oblimin),

CFA] |

Likert (5), SDA = 1;

SA = 5

[11-55] |

60

|

| Peters-2014 40 |

r |

Interview

(research visit) |

Convenience, 189 |

18–44, pregnant women (African American) |

- |

11 |

0.80,

R: ≥ 0.49 |

- |

[CFA],

Pcriterion validity |

Likert (5), SDA = 1; SA = 5

[24-55] |

67

|

| Hillen-2013 41 |

P |

Interview,

Self-report

(mail) |

NR, 175,

(70 %), [P, NR] |

≥ 18, cancer patients,

medical oncology and radiation oncology hospital dep. |

Fidelity, competence, honesty, caring, global trust |

33

(18) |

0.94

R = 43–.81 |

- |

CFA,

EFA,

correlations |

Likert (5), SDA = 1; SA = 5

[18-90] |

60

|

| Lori-2013 42 |

r |

Interview |

All available participants, 90, [42] |

≥ 18, maternity waiting homes, community

level health workers (trained traditional

midwives and certified midwives |

- |

40,39,16

(11) |

0.81* |

C:

Clarity, avoid repeating, eliminating

double-negative format items |

[EFA, (varimax, oblique), scree plot],

Pvalidity of: contrast,

& convergent |

Dichotomous: agree; disagree truth or

lies’ |

78

|

| Dinc- 2012 43 |

P |

Self-administered |

Multistage random, 232, [10] |

18–65,

hospitalized patients |

Trust in health care:

providers, payers, institutions |

17 |

0.87

R = 0.67

R Split-half = 0.67 |

C:

compatibility for forward-backward translation, modification |

[EFA, PCA (Varimax)

CFA] |

Likert (5), SA = 5;

SDA = 1

[17- 85] |

FGD, expert opinion &

55 |

| Bova- 2012 44 |

r |

Survey

(mail) |

Random, 150,

(43 %),[30] |

≥ 18, chronic health conditions |

Interpersonal connection, respectful professional partnering |

15

(13) |

0.96

R = 0.40- 0.84 |

C: rewording |

[Factor analysis, PCA (Varimax)] |

0 – 4

[0–52] |

56

|

| Eisenman- 2012 45 |

P |

Computer-assisted telephone

interview |

2-phase, Random-digit-dialed telephone, computer-assisted telephone interviewing system, 2588, (59.1 %), [P, NR] |

≥ 18,

Asian and African

American |

Honesty, fairness, competency, confidentiality |

4 |

0.79.

R:0.73-0.78 |

NR |

[PCA] |

Likert (5),

No confident = 1; very confident = 4, [4-16] |

literature review & community FGD |

| Jeschke- 2012 46 |

r |

Self-report |

Consecutively invited by midwives, 221 |

19–45,

expectant mothers, maternity ward of a general hosp. |

- |

15,13

(11) |

0.79 |

C: removal of

similar items, rephrasing |

[PCA (Varimax)],

Pexternal validity |

Likert (7), very = 1;

not at all = 7

[11-77] |

Literature, interviews of midwives mothers |

| Hillen- 2012 47 |

P |

Self-report |

Patients visiting

Oncology dep., 423, (65 %), [12] |

Cancer,

academic hosp. |

Competence, fidelity, confidentiality, honesty,

caring, global trust |

33

(18) |

High |

C: difficulty of items, wording and relevance for trust |

[EFA

(oblimin)

CFA], correlations |

Likert (5), SDA = 1; SA = 5 |

3,64,65,67,79 &

Item Pool for60 |

| Thom- 2011 48 |

r |

NR |

Recruited from a preceding study of homeless or marginally housed, HIV positive adults, 61 PHC clinician, 168 patients [14] |

HIV-positive adults, |

- |

18

(12) |

0.93 |

C: modification in wording, |

[EFA using polychoric

correlation matrix, ML,

(promax)],

Pconvergent validity, Pdiscriminant validity |

Likert (5),

No confident = 1; completely confident = 5

[12-60] |

physician FGD, semi structured individual interviews

&

80-83 |

| Montague- 2010 49 |

P |

Self-report |

Randomly invited, 101, [P,

NR] |

18-38,

women who used electronic fetal monitor |

Trust in:

care provider, medical technology, using technology |

80 |

0.92 |

C: revised when necessary, wording, format, or item position |

[PCA],

PValidity (structure, external, consequential), PGeneralizability |

Linacre (3)

1 = disagree 2 = neutral, 3 = agree

[80-210] |

84,85

|

| Radwin-2010 50 |

r |

Self-report |

Random, single acute care setting, 187, [P,

NR] |

Hospitalized cancer patients hematology-oncology setting |

- |

(5,4) |

0.77,

0.82 |

NR |

[CFA, ML,

EFA, PCA],

Pconstruct validity |

Likert (5),

never = 1; always = 6

[5-30,4-24] |

- |

| Zhang- 2009 51 |

r |

Self-administered |

Convenience, 1196,

(41 %), [77] |

≥ 18 |

Technical competence, benevolence |

18

(12) |

0.83 |

C: clarity, relevance, avoid using negative worded,

minimize confusion

PF |

[EFA, CFA, partial correlation matrix, (Varimax)]

Pconvergent validity by R |

Likert (5,7),

SDA = -3; SA = 3

[-36-36] |

Literature &

67,86,87

study team FGD |

| Bachinger- 2009 52 |

P |

Self-report |

Random, 201,

(52 %) |

19-88, of internal medicine patients |

Competence, honesty, fidelity, global trust |

10 |

0.88,

R:45 |

- |

[EFA (direct oblimin),

CFA], correlations |

Likert (5),

SA = 1; SDA = 5

[1.6–5.0] |

60

|

| Ngorsuraches- 2008 53 |

r |

Self-report |

Convenience,

400, [30] |

> 18, general population

public venues, such as shopping malls and bus stations |

Fidelity, competence, confidentiality,

honesty,

global trust |

47,40

(30) |

0.74-0.91 |

C: relevance, ambiguity, clarity create, delete, and adjust revised (expert) |

[EFA, with PCA, (Promax), Scree test],

correlation |

Likert (5),

SA; SDA

[NR] |

Expert reviews, FGD, think aloud method &

61,64,65,88 |

| Rotenberg- 2008 54 |

r |

Self-report |

Drawn from two

schools, 391 |

5-6 of elementary school children’s parents |

Honesty, emotional, reliability |

12

(9) |

0.70 |

- |

[PCA, CFA, (promax)],

PCorrelatio,

Pinter-correlation,

Convergence |

Likert (5),

trust very

much = 1;

I don’t trust at all = 5

[9-45] |

89-91

|

| Egede- 2008 55 |

r |

Self-report |

Convenience, 301, [256] |

University students,

primary care academic medical center |

- |

70

(17) |

0.86

Using R |

C: revised |

[EFA, orthogonal set of correlated factors, PCA (Varimax)] |

Likert (5), SA = 5;

SDA = 1

[17-85] |

2,8,58,60,61,65-67,92-98 & expert opinion |

| Bova- 2006 56 |

r |

Semi-structured focus group, Interview |

Purposeful (mail, phone,

directly by a team), 99, [10] |

≥ 18, living with HIV, primary care sites |

Knowledge sharing,

emotional connection, professional

connection, respect, honesty,

partnership |

58,30

(15) |

0.92

Using test–retest |

C: relevance, clarity, applicability, appropriateness of the response options, alternative wording

for awkward or confusing items |

[Exploratory PFA, (varimax )] |

Options (5), no time = 0; all the time = 4

[27-60] |

FGD,

interviews of HIV-infected adults |

| Kelly- 2005 57 |

r |

Phone, interview, mail |

Selected from ED log recently received care, 383, [238] |

Urban teaching hospital serving ED patients |

Eight factors(but not reported domains) |

42

(18) |

0.88 |

C: ambiguity, redundancy,

or unsuitability,

PF |

[PCA(Varimax)] |

Likert (5),

SDA = 1; SA = 5

[18-90] |

67

& staff feedback,

FGD,

in-person & telephone interviews |

| Dugan- 2005 58 |

r |

Telephone interview

(computer

assisted) |

Random-digit dialing, Random, National

(1064)

Insurance

(1045) |

≥ 21 |

Competence, motivation, honesty, confidentiality |

(5,5,5) |

0.87,

0.84,

0.77 |

Feasibility analyses for completeness,

floor and ceiling effects, and the dispersion of scores |

[Exploratory iterated principal components

factor analysis], Correlations

PConstruct validity Pconcurrent validity |

Coded

SA = 1; SDA = 5

[5-25] |

60,88

|

| Freburger- 2003 59 |

r |

Survey

(mail) |

Outpatient visit, 713,

(42 %) |

Patients (rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia rheumatology clinic from hosp. or private practices) |

- |

15 |

0.87,

R: ≥ 0.40 |

- |

[Correlational

analyses and factor analysis, PCFA] |

Likert (5), SDA = 1; SA = 5

[0–100] |

8,67

|

| Hall-2002 60 |

r |

Telephone interview |

Random, National 1117

Regional 1199, [108] |

> 21, households |

Fidelity, competence, confidentiality, honesty,

global trust |

78

(10) |

0.93 (national)

0.92 (regional) |

C: modification |

[EIPFA (varimax, promax)], correlation |

Likert (5),

SA-

SDA

[10-50] |

Medical setting1,92,99-102

Nonmedical settings12,103-115

previous scales,8,60,64,67,88 study team |

| Hall-2002 61 |

r |

Telephone interview |

Random

(residential telephone), 502, [8] |

Adult, regular physician and source of payment |

Fidelity, competence (technical, interpersonal), confidentiality, honesty,

global trust |

25

(11) |

0.89 |

C:

modification |

[EIPFA, (varimax promax), scree plot], Pconstruct validity: R |

Following Kao,1998

[11 to 55] |

Medical trust,1,2,66,116

Other,109,117,118 FGD, expert reviewers |

| Straten- 2002 62 |

NR |

Telephone interview, Interview |

Simple systematic, 1500, (70 %), [100] |

General |

Trust in: the patient-focus of health care providers; macro policies; expertise; quality of care; information supply and communication, quality of cooperation, the time spent on patients, availability of care |

37 |

0.80,

R among dimensions 0.20- 0.69. |

- |

[PCA, (oblique)] |

Likert (4),

very low - very high trust

[NR] |

The original phrases in the qualitative interviews were employed to describe the items. |

| Leisen- 2001 63 |

r |

Self-administered |

Random,

internal mail system), 214,

(23 %), [40] |

Employees of a service organization |

evaluating problems thoroughly, understanding patients’ experiences, expressing caring, providing appropriate and effective treatment, communicating clearly and completely, building partnership and sharing power, demonstrating honesty and respect for patients, predisposing factors, structural/staffing factors, keeping information confidential |

25

(11) |

0.8-0.9 |

C: clarity, relevance |

[CFA],

PValidity (convergent, discriminant, criterion) |

Likert (7)

[NR]

SDA = 1 SA = 7

[NR] |

66,67

|

| Thom- 1999 8 |

r (Modified) |

Self-administered |

Consecutive,

6-month follow-up, 440,

(67 %), [193] |

Adult diabetes patients in community-based, primary care practices |

- |

11 |

0.89,

ICC = 0.77 |

C: modified |

PValidity (construct, predictive ) using R, ANOVA |

SDA = 1;

SA = 5

[7-100] |

67

|

| Safran- 1998 64 |

r |

Patient-completed |

Random sample of employees

stratified by health plan, 6094,

(68.5 %),[500] |

Adult |

Assessment of primary physician’s integrity,

competence and role as the patient's agent |

11 |

0.86,

ICC = 0.44 |

C: completeness, score distribution |

Correlations (equal item variance, equal item-scale),

PValidity (item-convergent,

Item discriminant) |

Likert (5)

[0-100] |

Authors |

| Kao- 1998 65 |

r |

Telephone interview |

Two stage stratified, 300

(61 %) |

Adult with managed care |

Access to specialist, informing patients,

general trust |

10 |

0.94 |

C: modified |

NR |

Likert (5),

completely - not at all |

66,67

|

| Thom and Campbell- 1997 66 |

r |

Self-reported experiences |

Random, 29 |

26-72, diverse settings, patients, family practice clinic |

- |

- |

- |

C: accuracy |

- |

NR |

- |

| Anderson- 1990 67 |

r |

Interview, Telephone interview |

NR, 106,

(92 %, 77 %),[160] |

Outpatient clinic cases |

Dependability in look out, knowledge and skills, confidentially and reliability of information |

25

(11) |

0.90,

R = adequate |

C: clarity |

[Correlation] |

Likert (5), SA- SDA

[NR] |

119,120

&

interviews patients and

health care providers |

λ: Eigenvalue, NR: Not Reported * Kuder-Richardson's α (for dichotomous variables), # SF: Short Form, R: Correlation, SHR: Spearman-Brown Reliability coefficient (split half), EFA: Exploratory Factor Analysis, PAF: Principal Axis Factoring, PCA: Principal Component Analysis, EIPFA: Exploratory Iterated Principal Factor Analysis, ANOVA: Analysis of Variance, SA: Strongly Agree, SDA: Strongly Disagree, FGD: Focus Group Discussion, ICC: Intraclass Correlation Coefficient, CVR: Content Validity Ratio, CVI: Content Validity Index, Ô:references for item generation, P: done, PPS: probability proportional to size, MD: My Doctor, DiG: Doctors in General, HCT: Health Care Team.

Trust in Medical Scales’ Research Subjects in Studies up to 2023

In terms of trust scales subjects (52 studies), about 71 % (n = 37) of the scales were measuring trust in the medical profession (among them physician (n = 17), nurses (n = 6), care providers (n = 4), oncologist (n = 4), midwifery or maternal healthcare workers (n = 3), pharmacists (n = 2), dentists (n = 1)). Also, health care systems14 % (n = 7), emergency department (n = 1), trauma care department (n = 1), and health care team (n = 1) were trust in medicine scales subjects. The rest involved public health authorities, health insurers, COVID-19 control and prevention policies, telemedicine care or telehealth, medical technology, physician trust in the patient, performance, and general trust.

The current study found that different dimensions for measuring trust have been expressed in different studies which may be classified into one,16,18,23,26,33,35,37,40,41,44,45,47,50,52,58,60,61,64,67 two,4,2,25,28,34,39,42,48,59,63 three,17,29,43,49,51,53-56 four,32,46 five,17,36,57 six,10,38,62 seven,24 and nine66 dimensions.

Initial Dimensions of Trust in Medical Care Questioners Designed for Trust Studies

About 57 % (n = 30) of trust in medical care questioners designed for trust studies have reported initial or conceptual dimensions, although all the references used in the studies are mentioned in the item generation sources section (Table 2).

Final Dimensions of Trust in Medicine in Scales Designed for Trust Studies (up to 2023).

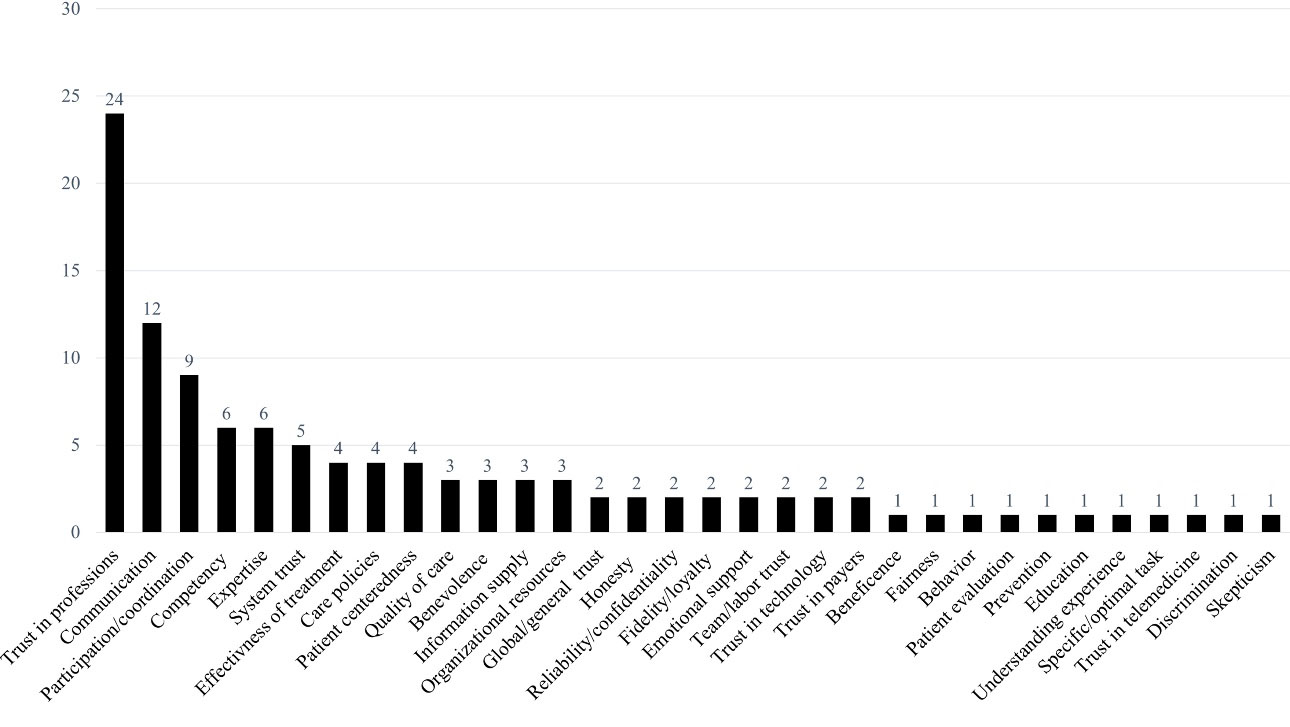

Figure 2 provides the final dimensions of trust in medical care in instruments developed for trust studies up to 2023.

Out of 100 % (113) reported domains, trust in professions was reported in 21 % (n = 24) of these studies. Communication (respectful interpersonal connection) was described in 11 % (n = 12) of these studies, participation (coordination) was disclosed in 8 % (n = 9) of studies, and competency and providers’ expertise (professional skill) were noted in 5 % (n = 6) of these studies. System (institutions) trust was announced in five studies, and effective treatment, care policies at the macro level, and patient-centered (focus) have been expressed 4 times each in studies.

Figure 2.

Frequency of final dimensions of trust in medicine in instruments designed for trust studies up to 2023

.

Frequency of final dimensions of trust in medicine in instruments designed for trust studies up to 2023

Quality of care, benevolence, information supply, and organizational resources were revealed three times each in studies. Also, general trust, honesty, reliability or confidentiality, emotional support, team or labor trust, trust in technology, and trust in payers were each recorded twice in these articles as a domain. Beneficence, fairness, behavior, patient evaluation, prevention, education, understanding experience, specific or optimal tasks, trust in telemedicine, discrimination, and skepticism were narrated as a domain in these studies. Four of these studies reported factors or domains without a specific name.

Trust in Medicine Correlates (Associates) in Developed Tools for Trust Studies in the Literature

Trust correlates are considered in ten categories including care, patient behavior, healthcare-patient, care provider professional, healthcare organization, personal health status, social, demographic, insurer, and other characteristics.

Healthcare-related characteristics included patient satisfaction, continuity, quality of care, public health behavior, accessibility, interpersonal treatment, comprehensiveness, service use/acceptance, patient-centeredness, and parent experience (Table 3).

Table 3.

Trust correlates in developed scales in medical care in the literature up to 2023

|

Trust correlates categories

|

No. (%)

|

| Healthcare related characteristics |

27 (15) |

| Patient Satisfaction |

14 |

| Continuity |

3 |

| Quality of care |

2 |

| Public health behavior |

2 |

| Accessibility |

1 |

| Interpersonal treatment |

1 |

| Comprehensiveness |

1 |

| Service use/acceptance |

1 |

| Patient centeredness |

1 |

| Parent experience |

1 |

| Patient behavior |

38 (21) |

| Adherence |

11 |

| Number of physicians visits |

9 |

| Choice |

5 |

| Seeking a second opinions |

4 |

| Returning for care |

3 |

| Independent decision making |

2 |

| Routine health exam/ health seeking |

2 |

| Membership in managed care |

2 |

| Healthcare-patient |

18 (10) |

| Unwillingness to switch |

7 |

| Recommendation |

6 |

| Previous experience |

3 |

| Pain manageability |

2 |

| Healthcare provider |

25 (13) |

| Length of relationship |

5 |

| No prior disputation |

5 |

| Behavior |

4 |

| Trust |

3 |

| Type of service provider |

2 |

| Expertise |

1 |

| Interaction |

1 |

| Trust the information from provider |

1 |

| Number of physician in practice |

1 |

| Educational grade of care provider |

1 |

| Graduated place |

1 |

| Healthcare organization |

6 (3) |

| Trust in healthcare system |

4 |

| Integration |

1 |

| Health plan |

1 |

| Health status |

18 (10) |

| General health |

5 |

| Health locus of control |

5 |

| Mental health |

4 |

| Physical health |

1 |

| Fibromyalgia or osteoarthritis |

1 |

| Schizophrenic |

1 |

| Depression |

1 |

| Social factors |

18(9.8) |

| General trust |

3 |

| Minority* |

3 |

| Racism specially in health care |

2 |

| Interpersonal trust |

2 |

| Racism specially in health care |

2 |

| Federal government |

1 |

| Ethnic identity |

1 |

| Social desirability |

1 |

| Social support |

1 |

| Partner’s support |

1 |

| Macro-level policy |

1 |

| Demographic features |

29(15) |

| Age |

10 |

| Education |

9 |

| Income |

3 |

| Nationality |

3 |

| Sex/gender |

2 |

| Marital status |

1 |

| Job |

1 |

| Insurer |

2(1) |

| Method of payment |

1 |

| Incentives for opportunistic behavior |

1 |

| Oher characteristics |

4(2.3) |

| Friend referral |

3(1.7) |

| Skepticism# |

1(0.5) |

|

Total

|

185

|

*Minority can be both a social characteristic and a demographic feature.

#Skepticism can take different forms, whether it's exhibited by patient-related behavior or within a social context.

Patient behavior covers features such as adherence, number of physician visits, choice, seeking a second opinion, returning for care, independent decision-making, routine health exams or health-seeking, and membership in managed care.

Care-patient features include unwillingness to switch, recommendation, previous experience, and pain manageability.

Care provider include elements like length of relationship, disputation, behavior, trust, type of service provider, expertise, interaction, trusting information from provider, the number of physicians in practice, educational grade of care provider, and graduated place.

Healthcare organization characteristics included institutional trust, integration, and health plan. Health status comprised general health, mental health, physical health, health locus of control, depression, fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, and schizophrenic.

Social categories include general trust, minority, racism especially in health care, interpersonal trust, racism especially in health care, the federal government, ethnic identity, social desirability, social support, partner’s support, and macro-level policy. Demographics include characteristics such as age, education, income, nationality, sex/gender, marital status, and job.

Insurer categories included methods of payment and incentives for opportunistic behavior. Other characteristics included friend referral and skepticism.

Items Numbers, Variances for Domains, Eigenvalue, Reliability, and Scoring of Trust in Medicine Developed Tools in the Literature

On average, 18 final items were obtained in each tool with a maximum and minimum of 80 and 4 cases, respectively. On average, 3 dimensions have been obtained in each tool, single dimension is the most frequent with 35 %, and the maximum dimension was reported in seven domains. Most of the studies reported variances of 54 % (n = 28), with a minimum of (3.3 %), and with a maximum of (82 %). Thirty-eight percent (n = 20) reported eigenvalue (λ) in the developed tools. The average reliability of the studies was 86.44( ± 7.26) with max = 0.98, and min = 0.68. Most of the studies used a 5-point Likert-type scale (82 %). Two of the studies used a 4-point Likert-type scale (Table 2).

Validity Status in Developed Scales in Medical Care (n = 52)

Exploratory factor analysis was used in 46 % (n = 24) of studies. Confirmatory factor analysis was used in 38 % (n = 20) of the studies. Convergent validity was used in 17 % (n = 9) of the studies. Criterion validity was applied in two of the studies. External validity was used in two of the studies. Regarding content validity clarity, wording, relevancy, semantic equivalence, item position, and grammatical/linguistic were the most common properties, respectively (Table 2).

Discussion

This is the first study to undertake a scoping review of all available evidence of instruments designed for measuring trust in medical care in the world up to 2023. This study was conducted to identify dimensions of trust in medical care, common trust subjects, and correlates, comprehensively.

Trust in professions, communication, participation or coordination, competency, expertise, system trust, effectiveness, care policies, patient-centeredness, quality of care, benevolence, informed care, resources, general trust, honesty, reliability, fidelity, and support were the most prevalent dimension of trust in medicine, respectively. Furthermore, beneficence, fairness, behavior, patient evaluation, prevention, education, understanding experience, specific task, trust in telemedicine, no discrimination, skepticism each were seen once as dimension of trust in medicine in literature studies.

The diversity in different dimensions of trust tools in the medical field can be caused by the sample size, disease-specific, study design, subject of trust, level of measurement, department or institution, time of study, time saving, and uniqueness of a language, type of specialties, data collection method, and location under investigation. Future research should, therefore, concentrate on the investigation of trust in medicine dimensions. “Trust will not be the same at all times and in all places”.121

Considering that there is a priority for one-dimensional scale, it may be conceivable to measure patients’ trust through a shorter form. Such a shortened form would be of specific intrigue for investigations including time-saving.18 A brief scale would reduce the patient and investigator burden, especially in investigations in which trust is not the essential focus.18 Due to the subjective nature of patient trust and its crucial importance in the physician-patient relationship, it is imperative to employ specialized instruments which are tailored to particular patient populations in the quantitative assessment of patient trust.39

Tool development studies in the field of trust in medicine have identified many correlates of trust in medicine which fall into nine general categories. These characteristics are related to healthcare (such as quality of care, patient-centeredness, acceptance, patient satisfaction …), patient behavior, healthcare-patient, care provider professional, healthcare system, individual health status, social factors, demographics, insurer, and other characteristics.

The results of this study showed that trust in medicine is closely related to all factors affecting the survival of the health organization, including the customer (patient), service provider, organization, and social systems. Trust acts as the glue that holds the system together.122 The decreasing trust is a sign of the quality of care decline of the systems that need attention to improve the family of trust to continually quality improvement. The existence of trust is the factor of people’s cooperation and their participation in public spheres and normal behaviors. The coronavirus pandemic showed that lack of trust leads to people’s non-cooperation which in turn brings about poor consequences.123-126 It is suggested that trust building should be seriously included in the main program of management and leadership of health organizations.

Based on the findings of the present study, the following themes are suggested for future research towards building confidence in medicine scales: It is advised that the association of these factors is investigated in future studies. In developing tools, we need to pay attention to the most common dimensions of trust. Measurements of trust in medicine have implications for clinical practice by influencing therapeutic patient-provider relationships, patient engagement, adherence to treatment plans, perception of quality of care, satisfaction, and ultimately, patient outcomes. Trust in medical care and public health is crucial for the well-being of individuals and society as a whole.

The emergency department is one of the important and busy departments127,128of the clinical settings that may have a significant impact on the satisfaction of the patients129,130 which should be given more attention in measuring the trust and satisfaction of the patients.

Although this scoping review research extends our knowledge of measuring trust in medicine, it has some restrictions. The biggest drawback of this study was that it only looked at literature in English and Persian, even if there may be worthwhile studies in other languages that were left out of the current synthesis. Another drawback of this study is the subjective interpretation of the results. Also, we did not evaluate the quality of each of the included studies.

Further investigation and experimentation into measuring trust in medical care is strongly recommended. It is recommended that further research in the development of tools related to the measurement of trust in medicine should pay attention to the most frequent dimensions and correlates of family of trust.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive view of the discussion of creating and developing tools in the field of medical care trust. However, existence of trust is an important factor, especially in the provision of medical and health practice. Trust in professions, communication, participation, competency, expertise, system trust, effectiveness, policies, patient-centeredness, quality of care, benevolence, informed care, resources, general trust, honesty, reliability, fidelity, and support were the most widespread dimensions of trust in medicine. The findings from this study make several contributions to the current literature. First, researchers in the field of trust are recommended to pay more attention to the most commonly known domains in preparing tools. Second, medical care providers and authorities need to consider the most common dimensions for the improvement of trusted care as an important index of healthcare quality improvement for future practice.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of a larger study and extracted from a doctoral dissertation. Authors appreciate road traffic injury research center of Tabriz university of medical sciences (Number: 66846). The authors would like to appreciate the cooperation of the Clinical Research Development Unit, Imam Reza General Hospital, Tabriz, Iran, in conducting this study.

COI-Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethical Approval

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran with No. IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.1098. All methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki (DoH).

Research Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

-

The measurements of trust in medical care have significant implications for clinical practice and patient care.

-

This enables healthcare providers to deliver patient-centered care, which is a crucial aspect of ensuring high-quality healthcare.

What is new here?

-

This investigation has revealed that trust in professions, communication, participation, competency, expertise, system trust, effectiveness, policies, patient-centeredness, quality of care, benevolence, information supply, resources, general trust, honesty, reliability, fidelity, and support is the most prevalent dimension of trust in medicine.

Supplementary File

Table S1. Search strategy in PubMed

(pdf)

References

- Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra AK. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: what is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Q 2001; 79(4): 613-39. what is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Q 2001; 79(4):what is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Q 2001; 79(4). doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00223 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D, Meyer S. Concepts of trust among patients with serious illness. Soc Sci Med 2000; 51(5):657-68. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00014-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hillen MA, Onderwater AT, van Zwieten MC, de Haes HC, Smets EM. Disentangling cancer patients’ trust in their oncologist: a qualitative study. Psychooncology 2012; 21(4):392-9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1910 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aloba O, Mapayi B, Akinsulore S, Ukpong D, Fatoye O. Trust in Physician Scale: factor structure, reliability, validity and correlates of trust in a sample of Nigerian psychiatric outpatients. Asian J Psychiatr 2014; 11:20-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.05.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Collins TC, Clark JA, Petersen LA, Kressin NR. Racial differences in how patients perceive physician communication regarding cardiac testing. Med Care 2002; 40(1 Suppl):I27-34. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201001-00004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zarei E, Daneshkohan A, Khabiri R, Arab M. The effect of hospital service quality on patient’s trust. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2015; 17(1):e17505. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.17505 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dinç L, Gastmans C. Trust in nurse-patient relationships: a literature review. Nurs Ethics 2013; 20(5):501-16. doi: 10.1177/0969733012468463 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Thom DH, Ribisl KM, Stewart AL, Luke DA. Thom DH, Ribisl KM, Stewart AL, Luke DAFurther validation and reliability testing of the Trust in Physician ScaleThe Stanford Trust Study Physicians. Med Care 1999; 37(5):510-7. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hillen MA, de Haes HC, Smets EM. Cancer patients’ trust in their physician-a review. Psychooncology 2011; 20(3):227-41. doi: 10.1002/pon.1745 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimipour H, Heidariyan Miri H, Askarzadeh E. Validity and reliability of measurement tool of public trust of health care providers. J Paramed Sci Rehabil 2020; 9(1):81-90. doi: 10.22038/jpsr.2020.41802.1988 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rowe R, Calnan M. Trust relations in health care--the new agenda. Eur J Public Health 2006; 16(1):4-6. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Baier A. Trust and antitrust. Ethics 1986; 96(2):231-60. doi: 10.1086/292745 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ozawa S, Sripad P. How do you measure trust in the health system? A systematic review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 2013; 91:10-4. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gopichandran V, Chetlapalli SK. Dimensions and determinants of trust in health care in resource poor settings--a qualitative exploration. PLoS One 2013; 8(7):e69170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069170 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Suhonen R, Saarikoski M, Leino-Kilpi H. Cross-cultural nursing research. Int J Nurs Stud 2009; 46(4):593-602. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.09.006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Stolt M, Charalambous A, Radwin L, Adam C, Katajisto J, Lemonidou C. Measuring trust in nurses - psychometric properties of the Trust in Nurses Scale in four countries. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2016; 25:46-54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2016.09.006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gopichandran V, Wouters E, Chetlapalli SK. Development and validation of a socioculturally competent trust in physician scale for a developing country setting. BMJ Open 2015; 5(4):e007305. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007305 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hillen MA, Postma RM, Verdam MG, Smets EM. Development and validation of an abbreviated version of the Trust in Oncologist Scale-the Trust in Oncologist Scale-short form (TiOS-SF). Support Care Cancer 2017; 25(3):855-61. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3473-y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg 2021; 88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Peters MD, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Scoping reviews: Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. 2017. 10.46658/jbirm-20-01

- Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015; 13(3):141-6. doi: 10.1097/xeb.0000000000000050 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sarbazi E, Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Farahbakhsh M, Ala A, Soleimanpour H. Psychometric properties of trust in trauma care in an emergency department tool. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2023; 49(6):2615-22. doi: 10.1007/s00068-023-02348-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Richmond J, Boynton MH, Ozawa S, Muessig KE, Cykert S, Ribisl KM. Development and validation of the trust in my doctor, trust in doctors in general, and trust in the health care team scales. Soc Sci Med 2022; 298:114827. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114827 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Alaei Kalajahi R, Saadati M, Azami Aghdash S, Rezapour R, Nouri M, Derakhshani N. Psychometric properties of public trust in COVID-19 control and prevention policies questionnaire. BMC Public Health 2022; 22(1):1959. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14272-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Holroyd TA, Limaye RJ, Gerber JE, Rimal RN, Musci RJ, Brewer J. Development of a scale to measure trust in public health authorities: prevalence of trust and association with vaccination. J Health Commun 2021; 26(4):272-80. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2021.1927259 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bani M, Rossi E, Cortinovis D, Russo S, Gallina F, Hillen MA. Validation of the Italian version of the full and abbreviated Trust in Oncologist Scale. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2021; 30(1):e13334. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13334 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Comparcini D, Simonetti V, Tomietto M, Radwin LE, Cicolini G. Trust in Nurses Scale: validation of the core elements. Scand J Caring Sci 2021; 35(2):636-41. doi: 10.1111/scs.12885 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Farahbakhsh M, Tabrizi JS, Zare Z, Saadati M. Psychometric properties of primary health care trust questionnaire. BMC Health Serv Res 2019; 19(1):502. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4340-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]