Journal of Caring Sciences. 13(4):256-266.

doi: 10.34172/jcs.33244

Original Article

Intention to Leave the Profession in Nursing: A Hybrid Concept Analysis

Sahar Dabaghi Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing, 1

Zohreh Nabizadeh-Gharghozar Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, 2, *

Armin Amanibani Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, 3

Author information:

1Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2Department of Pediatric Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3Student of Osteopathy (D.O) in Osteopathic College of Bordeaux, France

Abstract

Introduction:

Leaving the profession is a major challenge in all organizations throughout the world. Intention to leave the profession (ILP) is what individuals perceive about leaving the profession. Nurses’ perceptions of ILP are context-based and hence, studies in different contexts are needed to further explore ILP. The aim of this study was to analyze the concept of ILP, determine its attributes, antecedents, consequences, and provide a clear definition for it.

Methods:

This concept analysis was done using the hybrid model. In the theoretical phase, Magiran, Iran Medex, SID, Science Direct, Web of Science, PubMed, ProQuest, Scopus, and CINAHL databases were searched to retrieve ILP-related studies published in 2000–2023. In the fieldwork phase, semi-structured interviews were held with twenty nurses and nursing managers and the data were analyzed through conventional content analysis. In the final analysis phase, the results of the two former phases were compared and integrated.

Results:

ILP can be defined as "a voluntary and gradual process occurred due to professional disinterest, negative professional attitude, and unmanaged organizational stress and is associated with reduced job motivation, fatigue, and thoughts about leaving the profession which eventually leads to decision about staying in or leaving the organization".

Conclusion:

ILP is affected by many different personal, interpersonal, occupational, professional, organizational, environmental, and social antecedents and is associated with different patient, nurse, care-related, and organizational consequences. Nursing authorities and managers need to employ strategies to manage ILP antecedents and thereby, reduce nurses’ ILP.

Keywords: Intention, Concept analysis, Nursing

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Author(s).

This work is published by Journal of Caring Sciences as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Funding Statement

The study has no funding.

Introduction

Leaving the profession is a major global challenge in all organizations, irrespective of their types or geographical locations.1 By definition, leaving the profession is the withdrawal of workforce from an organization in a given period of time.2 Two review studies estimated that the rate of leaving the profession was 4%–68%.3,4 A cross-sectional study in European countries showed that 33% of nurses intended to leave their profession and 9% of them eventually left their profession.5 A study in Taiwan also showed that 56.1% of nurses intended to leave nursing and 2.5% of them left their profession in one year.6 Other studies reported that the rate of intention to leave the profession (ILP) in nursing was 32.7% in Iran,7 35.5% in Italy,8 and 67.8% in Ethiopia.9

Employees play significant role in organizational success and survival10and hence, organizations spend heavy costs on empowering their employees and improving their knowledge, skills, and performance.11 Therefore, leaving the profession among nurses imposes heavy costs on governments and healthcare organizations.12 Studies showed that the financial cost of leaving the profession per nurse was 48 790 dollars in Australia, 20 561 dollars in the United States, 65 226 dollars in Canada, and 71 123 dollars in New Zealand.13 Leaving the profession is also a major cause of staff shortage which is an international challenge in nursing.14 Moreover, leaving the profession among nurses negatively affects care quality and nurses’ well-being, imposes financial strains on hospitals,15 and requires healthcare organizations to recruit novice nurses. Limited skills and efficiency among novice nurses are in turn associated with reduced competition, innovation, and care quality.16

ILP is a multifactorial phenomenon determined by many different factors such as occupational, personal, and organizational factors. Occupational factors include limited job satisfaction, limited workplace safety, work style, organizational and managerial factors, workplace tensions, mandatory overtime work, low salaries, long work shifts, high expectations, staff shortage, and workplace characteristics. Personal factors include age, work experience, educational level, and self-confidence, personal errors due to heavy workload, and limited competence and self-efficacy to manage new clinical conditions.17-19

ILP is a good predictor of the rate of actual leaving of the profession.20,21 ILP is the cognitive step before actual leaving of the profession and refers to a mental decision whether to stay in the profession or not.22 Evidence shows that ILP is based on a former awareness and readiness for leaving an organization. In other words, employees do not suddenly leave an organization; rather, they think about it over time, develop their ILP, consider the opportunity of employment in other organizations, and finally decide on staying in or leaving their organization.23

Despite the importance of ILP to the prediction of actual leaving of the profession, there are limited data about its attributes, antecedents, and consequences. A concept analysis into ILP revealed that ILP is a multiphasic process with negative psychological reactions to internal and external occupational contexts which may lead to turnover-related cognitions and behaviors and eventually make employees actually leave their organization.24 An integrative review also highlighted that demographic, work-related, and personal factors can affect ILP.3

Besides the paucity of data about ILP, the concept of ILP is context-based and hence, the available data in this area may not easily be generalizable to other contexts. Accordingly, further studies are needed to provide more in-depth data about ILP. Also, this analysis of the associations for nurses could help us improve our understanding of why members of the target group may wish to leave the profession. Implementing appropriate reforms to improve specific work conditions could lead to timely and specific prevention of departure from the profession. This would help retain the necessary staff in hospitals and ensure that Iranian hospitals continue to function efficiently. The present study was conducted to narrow this gap. The aim of this study was to analyze the concept of ILP, determine its attributes, antecedents, and consequences, and provide a clear definition for it.

Materials and Methods

This concept analysis was done using the hybrid model. The hybrid model is a method for conceptualization, concept development, and theorization which integrates both deductive and inductive methods to refine widely used concepts.25 The hybrid model is based on the existing literature and the experiences of involved individuals, provides a clear understanding about the concept of interest, and hence, is preferred over other methods for concept analysis.26 This model has three main phases, namely theoretical phase, fieldwork phase, and final analysis phase.27 The theoretical phase includes reviewing the relevant literature in order to discover the essence of the concept and the available definitions. In the fieldwork phase, the concept of interest is further explored and refined through a qualitative study. In the final analysis phase, the findings of the first and the second phases are compared and integrated and a clear and comprehensive definition is provided for the concept.26 The concept of ILP is significant in nursing science and practice. The lack of awareness around ILP can have huge implications for the healthcare system. Due to the ambiguities in the literature surrounding the concept of ILP, this concept was selected for analysis.

Theoretical Phase

In this phase, ILP-related literature was reviewed. Accordingly, an online literature search was performed in national and international databases, namely Magiran, Iran Medex, SID, Science Direct, Web of Science, PubMed, ProQuest, Scopus, and CINAHL. Search keywords were “intention to leave”, “turnover intention”, “intention to change job”, and “nurse” and search date was limited to 2000–2023. Eligibility criteria were inclusion of keywords in the title, relevance to the concept of ILP in nursing, publication in English or Persian, and accessible full-text. Letters to the editor, abstracts with no full-text, and commentaries were not included. A data sheet was used for data extraction. The items of the sheet were on study aims, methods, participants, ILP definitions, ILP attributes, ILP antecedents, and ILP consequences. Two authors independently evaluated the study quality based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009.

Fieldwork Phase

Design and Participants

A descriptive qualitative study was conducted in this phase to explore nurses’ experiences of ILP. Participants were twenty employed nurses, nurses with the history of leaving their service, and nursing managers. They were purposively selected with maximum variation respecting their age, work experience, work shift, and affiliated ward. Study setting was several hospitals in Tehran, Isfahan, and Kashan, Iran.

Data Collection

Data were collected through face-to-face semi-structured interviews. The main interview questions were, “Have you ever experienced ILP as a nurse?” “In which situations and conditions were you more intended to leave the profession?” “Why do employees stay in their organizations?” “How does ILP physically and emotionally affect you?” and “What strategies do you recommend to prevent ILP?” Probing questions such as “May you provide an example?”, “May you provide more explanations?”, and “What do you mean by this?” were also used to further explore participants’ experiences. Interviews were conducted in nurses’ lounge in the study setting by appointment. The length of interviews was fifty minutes on average. All interviews were digitally recorded. Data collection was continued to reach data saturation which was achieved after interviewing twenty participants. Saturation is achieved when data collection and analysis produce no more new data and all findings are fully developed.28

Data Analysis

Collected data were analyzed concurrently with data collection through the content analysis method proposed by Graneheim and Lundman.29 Each interview was transcribed word by word and the transcript was read for several times in order to immerse in the data. Then, meaning units were identified and coded and the codes were grouped into subcategories and categories according to their similarities.29 All authors of the study participated in data analysis.

Trustworthiness

Guba and Lincoln’s criteria were used to ensure trustworthiness. These criteria are credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability.30 Credibility was maintained through constant comparison, prolonged engagement with the data, and member checking by several participants. Dependability was ensured through external peer debriefing by two external qualitative researchers who assessed and confirmed the accuracy of data analysis. Moreover, detailed descriptions about the study context and the characteristics and experiences of participants were provided to ensure transferability. To ensure confirm ability, all steps of the study were documented so that other researchers can track the steps of the study.

Final Analysis Phase

In this phase, the findings of the first two phases were compared and combined, final subcategories and categories were developed, and a final definition for ILP in nursing was provided. Table 1 shows examples of data analysis in the three phases of the study.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics (n = 20)

|

Characteristic

|

No. (%)

|

| Age range (y) |

|

| 20-29 |

2 (10) |

| 30-39 |

7 (35) |

| 40-49 |

6 (30) |

| 50-59 |

5 (25) |

| Gender |

|

| Female |

13 (65) |

| Male |

7 (35) |

| Occupation |

|

| Nursing manager |

6 (30) |

| Nurse |

14 (70) |

| Work experience (y) |

|

| 0-9 |

6 (30) |

| 10-19 |

10 (50) |

| 20-29 |

4 (20) |

Results

Theoretical Phase

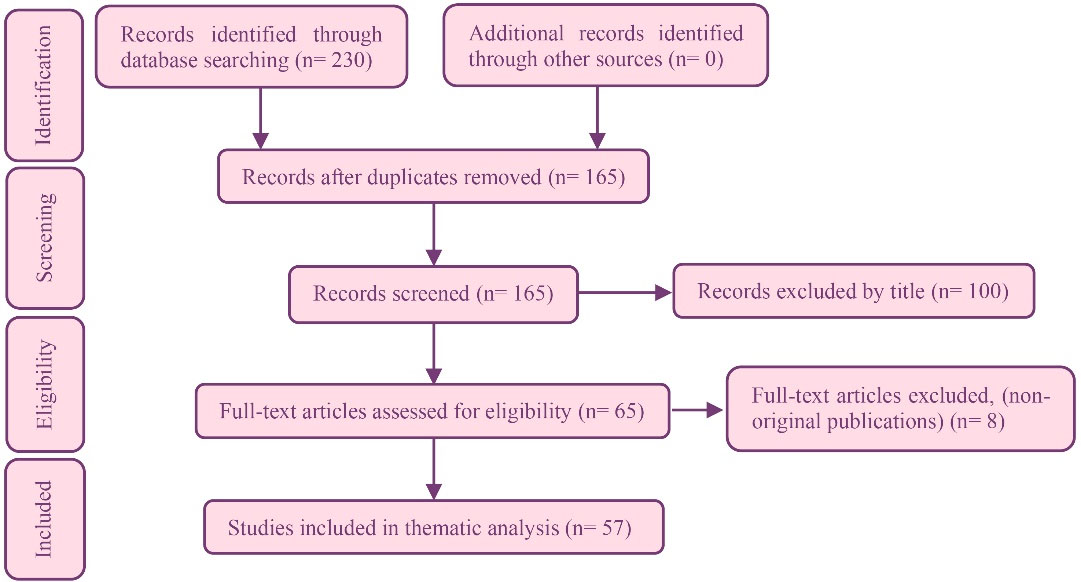

A total of 230 articles were found and 57 eligible articles were included in the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram for the selection of studies

.

PRISMA diagram for the selection of studies

Definition of the ILP Concept

Webster’s dictionary defines intention as “what one intends to do or bring about”. Some scholars defined ILP as a conscious and thoughtful desire to leave the organization.31ILP reflects employees’ interest to seek alternative jobs and leave the organization and is an indicator of actual leaving of the profession.32ILP is broadly defined as an attitudinal, decisional, and behavioral process for leaving the profession.33 Moreover, it is defined as the amount of movement an employee has towards cancelling membership in a social system and is started by the worker himself/herself.34 In other words, ILP is the conscious desire for resigning from an organization and leaving it and may not necessarily lead to actual leaving of the organization but denotes its possibility in a near future.35 Contrary to actual leaving of the profession, ILP is not manifest; rather it refers to thinking about leaving the profession in a given period of time and is an essential prerequisite for actual leaving of the profession.36

ILP Models

Based on ILP antecedents, there are two main types of ILP model, namely models based on organizational factors and models based on personal factors. Examples of the first type of models are the Deconinck and Stilwell’s model and the Gaertner’s model and examples of the second type of models are the Lee and Michel’s model and the Maertz and Griffith’s model.

Deconinck and Stilwell’s model: This model addresses the relationship of leaving the profession with organizational justice (consisted of distributive and procedural justice), role states, payment satisfaction, and supervisor satisfaction. It states that payment satisfaction is explicitly affected by distributive justice and implicitly affected by role states, while supervisor satisfaction is explicitly affected by procedural justice and role states. Moreover, payment satisfaction and supervisor satisfaction affect organizational commitment and thereby, determine ILP.37

Gaertner’s model: This model holds that payment, role ambiguity, role conflict, peer support, role expectations, autonomy, routinization, promotional chances, distributive justice, and supervisory support affect ILP through affecting job satisfaction and organizational commitment.38

Lee and Mitchell’s model: The major assumption of this model is a mental shock and analysis which happens before action. The shock forms the thought of leaving the profession and subsequently, the employee decides to either leave or stay in the organization.39

Maertz and Griffith’s model: This model states that eight main categories of motivational forces affect ILP. These categories are as follows:

Affective forces: Positive or negative forces which affect workers’ decision to stay in or leave the organization;

Calculative forces: Staying in or leaving the profession depends on the possibility to attain important values or goals in the organization;

Contractual forces: Refers to the perceptions of the level of reciprocal dependence of the organization and employees;

Behavioral forces: Entails the costs of leaving the organization;

Alternative forces: Refers to self-efficacy beliefs about obtaining alternative jobs or values in the organization or other organizations;

Normative forces: Refers to perceived expectations of family members or friends with respect to staying in or leaving the organization;

Moral forces: Refers to values and beliefs about leaving the organization;

Constituent forces: Refers to forces related to coworkers or groups in the organization.40

Antecedents of ILP

Antecedents of ILP in the theoretical phase came into four main categories, namely demographic factors, psychological factors, interpersonal factors, and occupational factors.

Demographic factors: Demographic factors such as gender, age, educational level, work experience, and marital status can affect ILP. Some studies reported higher ILP among men,41,42 while a study reported higher ILP among married women.43 Moreover, some studies reported that ILP had significant positive relationship with age and work experience,41,43 while some studies reported the significant negative relationship of ILP with age and work experience.44,45 Studies into the relationship of ILP and educational level reported contradictory findings.42,46

Psychological factors: Psychological factors such as stress, job burnout, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction can affect ILP. Occupational stress has significant positive relationship with ILP.18 The main sources of occupational stress are inadequate payment, work inequity, heavy workload, staff shortage, limited promotional chances, limited job security, and limited managerial support.17 Staff shortage and heavy workload are associated with job dissatisfaction and job burnout.47 Job burnout in turn has significant positive relationship with ILP.45,48 Organizational commitment and job satisfaction also have significant negative relationship with ILP.44,45,48

Interpersonal factors: ILP is also affected by interpersonal factors such as managerial style, managers’ characteristics, and leadership style, participation in decision making, social support, teamwork, and interpersonal relationships. Studies reported that perceived organizational justice,7 ethical leadership,49leadership style, positive perception of participation in organizational affairs,50 transformational leadership, managerial support,51 managers’ organizational power, and teamwork52 can reduce ILP. Moreover, interpersonal relationships, including nurse-nurse, nurse-manager, and nurse-physician relationships, can affect nurses’ mental health, professional performance, and productivity.53 Inappropriate workplace relationships may also make nurses leave their profession or organization.17

Occupational factors: Occupational factors such as quality of working life, workplace environment, and organizational culture may act as the antecedents of ILP. Employees with high quality of working life have stronger organizational identity, higher job satisfaction, and better occupational performance and are less likely to leave their job or organization.18 Professional respect and autonomy, two key components of the quality of working life, have significant relationship with ILP.6 Moreover, occupational control is associated with better quality of working life, lowers organizational indifference, and thereby, reduces ILP.54 Autonomy in decision making is a component of occupational control and has significant relationship with ILP.55 A significant factor in ILP is inappropriate work conditions consisted of heavy physical and mental workload, time pressure, shortage of equipment and staff, role ambiguity, and job instability.7,48 A study in ten European countries reported that ILP among nurses with positive workplace-related perceptions was 30% lower.5 Some studies showed that ILP had significant positive relationship with workplace violence,45 inappropriate workplace relationships,48 and occupational hazards,56 and had significant negative relationship with organizational culture.57,58 Organizational culture refers to a set of values, beliefs, and behavioral patterns which form the identity of an organization and the behaviors of its workers.57 A study reported that individuals in different countries have different values. For instance, collectivistic cultures are more common in Asian countries, while individualistic cultures are more common in western countries. Individuals in collectivistic cultures depend on each other and prefer groups over self, while individuals in individualistic cultures are independent and value their personal goals more than group goals. Accordingly, workers with collectivistic morale in Asian countries may be more satisfied with their workplace, show greater organizational commitment, and have lower ILP.58

Consequences of ILP

The consequences of ILP are patient-related, nurse-related, and organizational consequences.

Patient-related consequences: ILP can lead to staff shortage which is a leading cause of clinical errors. Errors in turn prolong hospital stay and increase healthcare costs, infection rate, and mortality rate.59,60 Moreover, leaving the profession requires organizations to recruit novice nurses to reduce staff shortage. Limited experience of novice nurses reduces competition, innovation, and care quality,16 negatively affects the provision of safe, fair, and effective patient-centered care, and reduces patient satisfaction with care.61

Organizational consequences: Leaving the profession is associated with reduced professional performance, reduced organizational productivity, increased workload, lower ability to adhere to ethical principles, and increased turnover of other employees. Moreover, it increases employment-related financial costs, alters organizational functions, and reduces organizational effectiveness16,62

Nurse-related consequences: The nurse-related consequences of ILP include undermined morale of workers, damage to peer relationships, reduced interactions, reduced sense of responsibility, change in roles, and senses of instability, detachment, and isolation.63,64

Fieldwork Phase

Participants in this phase were eight employed nurses, six nurses with the history of leaving their service, and six nursing managers (Table 1). A total of 650 codes were generated during data analysis which were grouped into three main categories, namely antecedents of ILP, strategies to reduce ILP, and consequences of ILP (Table 2).

Table 2.

ILP Antecedents, ILP consequences, and strategies to reduce ILP in the fieldwork phase

|

Categories

|

Subcategories

|

| ILP antecedents |

Social acceptance of the profession |

| Limited professional interest |

| Limited professional development |

| Unsafe work environment |

| Inappropriate work conditions |

| Managerial insufficiency |

| Strategies to reduce ILP |

Developing an appropriate organizational structure |

| Improving the quality of working life |

| ILP consequences |

Impaired care quality |

| Reduced organizational productivity |

| Mental problems |

Antecedents of ILP

The six main antecedents of ILP were social acceptance of the profession, limited professional interest, limited professional development, unsafe work environment, inappropriate work conditions, and managerial insufficiency.

Social acceptance of the profession: Participants’ experiences showed that the social acceptance of each profession depends on its responsibilities towards the society. Participants noted that the public image of nursing and social support for nurses can affect nurses’ self-confidence, resistance to different tensions, and ILP. They introduced unacceptance of nursing by the society, family, and other healthcare providers as the most important factors in nurses’ ILP.

“The social status of nursing is very important. Inappropriate nursing-related advertisements and content in media lead to the formation of unrealistic images of nursing. Television serials depict nurses as physicians’ handmaidens who just follow physicians’ orders. This poor media image of nursing questions nurses’ autonomy” (P. 9).

Limited professional interest: According to the participants, limited professional interest, negative attitudes towards the profession, and limited job motivation are among the most important antecedents of ILP. They noted that nurses with high job motivation experience interest and pleasure at work and highlighted the importance of nurses’ awareness of their nursing- and care-related attitudes, values, and expectations and their effects on nursing care.

“The very basic necessity is interest, meaning that you have to like nursing and patient care. Disinterest is associated with limited motivation for knowledge and skill development as well as discouragement. I worked in nursing without any motivation and finally decided to leave it” (P. 6).

Limited professional development: Limited changes in work characteristics over time, prolonged care provision in certain wards, and frequent performance of repetitive daily tasks can be associated with reutilization, senses of boredom and stasis, job burnout, and low job motivation and eventually move nurses towards leaving the profession.

“I started my mandatory post-graduation service in this ward and now it is for several years that I’m doing repetitive daily tasks in this ward. There is neither attraction nor creativity; rather, I repeat the same procedures every day in the same ward and the same rooms with the same colleagues. I’m really tired. Sometimes, I think about leaving the profession” (P. 7).

Unsafe work environment: Participants noted that inappropriate physical workplace environment, critical conditions in hospital wards, risk of affliction by infectious diseases, exposure to different dangerous chemicals and diagnostic and therapeutic radiations, and shortage of standard equipment and medications make nurses’ work environment unsafe and move nurses towards leaving the profession.

“I worked in infectious diseases ward, where there was neither adherence to clinical guidelines, nor appropriate personal protective equipment. I was always worried about affliction by infectious diseases or transmission of infectious diseases to my family members. I always liked a pleasant and safe work environment” (P. 11).

Inappropriate work conditions: Participants also reported heavy workload, rotational work shifts, long work hours, rest and sleep disorders, long waking hours, unfair payments, shortage of welfare facilities, and inappropriate employment opportunities as main occupational factors contributing to job dissatisfaction and ILP.

“The number of nurses’ work shifts is very high and their workload is heavy. Their documentation-related tasks are also heavy and tire them. On the other hand, their salaries are not proportionate to their services” (P. 18).

Managerial insufficiency: Participants highlighted that managers’ and authorities’ incompetence, unclear job specifications, inappropriate feedback and performance evaluation, injustice in rules and regulations, limited attention to care quality, and great emphasis on non-professional affairs significantly affect nurses’ ILP.

“I saw some colleagues did not adhere to the regulations but were not punished for their non-adherence because head nurse liked them. For example, they were not punished for late attendance at work and absence from work, while I was punished for such things” (P. 1).

Strategies to Reduce ILP

The two main strategies for reducing ILP were developing an appropriate organizational structure and improving the quality of working life.

Developing an appropriate organizational structure: Organizational structure refers to the roles of different employees and the pattern of relationships among the roles in the organization. In other words, organizational structure is role expectations and relationships. Organizational roles are usually determined through job descriptions and written documents. Our participants highlighted the necessity of meritocracy, clear job descriptions, effective workforce management, ethical practice, organizational justice, job security, and participatory decision making to develop an appropriate organizational structure.

“In each system, organizational structure should be so appropriate that all employees like to stay and work in the organization. In other words, each employee should be at his/her appropriate place based on his/her competence” (P. 13).

Improving the quality of working life: Quality of working life refers to employees’ satisfaction with occupational need fulfillment, resources, and activities. Participants highlighted that effective professional communication, fair and timely payment, benefits and rewards, and adequate health, welfare, and safety facilities for nurses can improve their quality of working life, quality of life, job motivation, and job satisfaction.

“Stronger support and better salaries should be provided to nurses. Nurses with lower financial problems can spend more energy at work. Organizational support is also needed to improve our motivation. By support, I don’t necessarily mean financial support; rather, I mean verbal encouragement about our activities” (P. 7).

Consequences of ILP

The three main consequences of ILP were impaired care quality, diminished organizational productivity, and mental health issues.

Impaired care quality: Participants noted that while nursing means effective care provision to clients, ILP can reduce nursing care quality through reducing nurses’ ability and motivation to pay close attention to their clients’ needs and values, use the nursing process, establish effective communication with clients, provide quality education to clients, develop their own professional knowledge and skills, provide care based on ethical principles, and use scientific evidence in practice.

“Care quality is not important for me; rather, I just want to finish work and go home. I have no mood for talking with patients, assess their needs, and provide them with education” (P. 12).

Diminished organizational productivity: Participants reported that ILP can be associated with different problems such as frequent absence from work, late attendance at work shifts, disharmony at work, non-adherence to organizational regulations, inattention to organizational goals, non-participation in continuing education and accreditation programs, and reduced satisfaction of patients, colleagues, and managers.

“Frequent absence of some nurses increases their colleagues’ workload, reduces their colleagues’ ability to provide professional care, and makes patients complain of not receiving the necessary services” (P. 17).

Mental health issues for nurses: Participants reported reduced self-confidence, fatigue, despair, disability, disinterest, low motivation, isolation, sense of humiliation and worthlessness, depression, low mood, cigarette smoking, drug abuse, psychological strains, and low job motivation as the mental consequences of ILP for nurses.

“I have a sense of humiliation. I work in a low-level and worthless profession and hence, I always feel despair. Sometimes, I feel remorse at selecting this profession” (P. 13).

Final Analysis Phase

Comparison of the findings of the first and the second phases in the final analysis phase revealed great similarities between findings (Table 3). The results of the theoretical phase revealed ILP as a conscious desire to leave the organization which is in agreement with the findings of the fieldwork phase. The only difference between the findings of these two phases was that participants in the fieldwork phase introduced some ILP antecedents which were not reported in the reviewed literature. Examples of these antecedents were reutilization, senses of boredom and stasis, and subsequent limited professional development. Moreover, participants in the fieldwork phase highlighted that ILP is a process which occurs due to stress caused by unmanaged personal and organizational challenges and reported that limited professional interest, negative attitude toward nursing, and organizational factors can affect ILP. Based on the results of the theoretical and the fieldwork phases, ILP can be defined as “a voluntary and gradual process occurred due to professional disinterest, negative professional attitude, and unmanaged organizational stresses and is associated with reduced job motivation, fatigue, and thoughts about leaving the organization which eventually leads to decision about staying in or leaving the organization”.

Table 3.

Examples of data analysis in the three phases of the study

|

Categories

|

Subcategories

|

| ILP antecedents |

Social acceptance of the profession |

| Limited professional interest |

| Limited professional development |

| Unsafe work environment |

| Inappropriate work conditions |

| Managerial insufficiency |

| Strategies to reduce ILP |

Developing an appropriate organizational structure |

| Improving the quality of working life |

| ILP consequences |

Impaired care quality |

| Reduced organizational productivity |

| Mental problems |

Discussion

This study aimed at analyzing the concept of ILP, determining its attributes, antecedents, and consequences, and providing a clear definition for it. Findings revealed ILP as a process occurred under the effects of contextual factors, such as personal and organizational challenges, which requires nurses to think about possible solutions to their problems, and may eventually lead to leaving the profession if they cannot successfully manage their problems. There are many different theories and models to explain leaving of the profession behavior of employees. Intention is the best predictor of behavior.65 Therefore, organizational authorities should develop effective strategies to identify and manage ILP antecedents in their organizations, prevent their employees from leaving their organizations, identify and fulfill employees’ needs, and thereby motivate them to stay in the organization. A study in Italy reported that the three main causes of nurses’ ILP were seeking for a better job (31%), seeking for better living conditions (28%), and seeking for better career advancement opportunities (11%).66

Our findings revealed that personal challenges such as limited professional interest and negative professional attitude were antecedents of thinking about leaving the profession. Similarly, a qualitative study on young nurses found limited interest in nursing and incongruence between mental and actual images of nursing as the reasons for ILP.67Another study also reported the significant relationship of professional interest with ILP among nurses.68 Traditional models of ILP, appeared in 1980–1990, included attitudinal models on job satisfaction, commitment, and seeking for alternative jobs.69 Non-traditional models, appeared after 1990, omitted the constructs of attitude and seeking for alternative jobs and introduced constructs such as organizational attachment and interpersonal differences as the main ILP antecedents.70 The limited professional interest antecedent of ILP in the present study is in agreement with the non-traditional models of ILP antecedents.

The findings of the present study revealed developing an appropriate organizational structure and improving the quality of working life as strategies to reduce ILP. In line with this finding, a previous study reported that occupational characteristics such as skill diversity, occupational identity, occupational importance, autonomy, and constructive feedback as well as organizational factors such as environmental conditions, rewards, and supervisory support can affect nurses’ organizational loyalty and ILP.71 Another study reported workload reduction as a significant factor in retaining nurses in the profession.21 Similarly, a study reported that hospital managers can improve nurses’ retention and reduce their ILP through improving work environment, generating positive psychological capital, and enhancing job satisfaction.72

We also found that nurses’ ILP has negative consequences for patients, nurses, and healthcare organizations. Therefore, nurses’ ILP should be reduced through strategies such as recruiting committed nurses to the profession and improving nurses’ professional commitment. Strategies for professional commitment improvement include improving work conditions, increasing work importance, and improving professional interest, while factors such as injustice in organization, inattention to employees’ needs, limited participation in organizational affairs, and limited professional interest can reduce professional commitment. Participation in organizational affairs and organizational decision making and effective communication with managers create an environment in which employees feel more job satisfaction and show more organizational commitment.73,74

It is worth mentioning that some factors, such as low wages for nurses in Iran, mandatory overtime due to the workforce shortage crisis in hospitals, and the differing acceptance and social status of the nursing profession in society, are undeniable.

Conclusion

This study concludes that ILP is affected by many different personal, interpersonal, occupational, professional, organizational, environmental, and social antecedents and is associated with many different patient-related, nurse-related, care-related, and organizational consequences. Developing ILP assessment instruments based on the findings of the present study is recommended for accurate ILP assessment and effective ILP prevention and management. Given the negative effects of ILP on care quality and organizational productivity, effective strategies are needed to improve clinical and organizational environments, nurses’ job satisfaction, and their professional development. Examples of these strategies are recruitment of competent nurses to the profession to reduce nurses’ workload and work hours, timely payments, education of communication skills, promoting autonomy in clinical decision making, clarifying job descriptions, improving self-confidence and organizational support, and using a supportive leadership style. These strategies will help nursing managers reduce and prevent ILP and thereby, reduce the heavy costs of recruiting, developing, and retaining nursing staff. Nursing education authorities can also use educational interventions to inform nursing students about the realities of nursing practice and help them make better decisions whether to stay in nursing or not.

One of the limitations of the present study was that, just English and Persian languages publications were analyzed. Therefore, some important works in other languages might have been missed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the participants whose contribution enabled the production of this paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

The Ethics Committee of Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran, approved this study (code: IR.KAUMS.NUHEPM.REC.1398.074). Participants were informed about the study aim, voluntariness of participation in and withdrawal from the study, and confidentiality of their data, and their informed consent was obtained.

Research Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

What is new here?

-

Intention to leave the profession can be defined as “a voluntary and gradual process occurred due to professional disinterest, negative professional attitude, and unmanaged organizational stress and is associated with reduced job motivation, fatigue, and thoughts about leaving the profession which eventually leads to decision about staying in or leaving the organization”.

References

- Lim A, Loo J, Lee P. The impact of leadership on turnover intention: the mediating role of organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling 2017; 1(1):27-41. doi: 10.47263/jasem.1(1)04 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rudman A, Gustavsson P, Hultell D. A prospective study of nurses’ intentions to leave the profession during their first five years of practice in Sweden. Int J Nurs Stud 2014; 51(4):612-24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.09.012 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Flinkman M, Leino-Kilpi H, Salanterä S. Nurses’ intention to leave the profession: integrative review. J Adv Nurs 2010; 66(7):1422-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05322.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sabanciogullari S, Dogan S. Relationship between job satisfaction, professional identity and intention to leave the profession among nurses in Turkey. J Nurs Manag 2015; 23(8):1076-85. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12256 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Heinen MM, van Achterberg T, Schwendimann R, Zander B, Matthews A, Kózka M. Nurses’ intention to leave their profession: a cross-sectional observational study in 10 European countries. Int J Nurs Stud 2013; 50(2):174-84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.019 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lee YW, Dai YT, Chang MY, Chang YC, Yao KG, Liu MC. Quality of work life, nurses’ intention to leave the profession, and nurses leaving the profession: a one-year prospective survey. J Nurs Scholarsh 2017; 49(4):438-44. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12301 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sokhanvar M, Kakemam E, Chegini Z, Sarbakhsh P. Hospital nurses’ job security and turnover intention and factors contributing to their turnover intention: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Midwifery Stud 2018; 7(3):133-40. doi: 10.4103/nms.nms_2_17 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sasso L, Bagnasco A, Catania G, Zanini M, Aleo G, Watson R. Push and pull factors of nurses’ intention to leave. J Nurs Manag 2019; 27(5):946-54. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12745 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Worku N, Feleke A, Debie A, Nigusie A. Magnitude of Intention to leave and associated factors among health workers working at primary hospitals of North Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: mixed methods. Biomed Res Int 2019; 2019:7092964. doi: 10.1155/2019/7092964 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Frank FD, Finnegan RP, Taylor CR. The race for talent: retaining and engaging workers in the 21st century. Hum Resour Plan 2004; 27(3):12-25. [ Google Scholar]

- Hassanzadeh R, Samavatyan H, Nouri A, Hosseini M. Relationship of supportive managerial behaviors and psychological empowerment with intention to stay in health care organization. J Health Syst Res 2013; 8(7):1206-15. [ Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Johanson MM, Guchait P. Employees intent to leave: a comparison of determinants of intent to leave versus intent to stay. Int J Hosp Manag 2009; 28(3):374-81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.10.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Duffield CM, Roche MA, Homer C, Buchan J, Dimitrelis S. A comparative review of nurse turnover rates and costs across countries. J Adv Nurs 2014; 70(12):2703-12. doi: 10.1111/jan.12483 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Boamah SA, Laschinger H. The influence of areas of worklife fit and work-life interference on burnout and turnover intentions among new graduate nurses. J Nurs Manag 2016; 24(2):E164-74. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12318 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Han K, Trinkoff AM, Gurses AP. Work-related factors, job satisfaction and intent to leave the current job among United States nurses. J Clin Nurs 2015; 24(21-22):3224-32. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12987 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Galletta M, Portoghese I, Battistelli A. Intrinsic motivation, job autonomy and turnover intention in the Italian healthcare: the mediating role of affective commitment. J Manag Res 2011; 3(2):1-19. doi: 10.5296/jmr.v3i2.619 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Taghadosi M, Nabizadeh Gharghozar Z, Bolandian Bafghi S. Intention to leave of nurses and related factors: a systematic review. Sci J Nurs Midwifery Paramed Fac 2019; 4(4): 1-14. [Persian].

- Jafari M, Habibi Houshmand B, Maher A. Relationship of occupational stress and quality of work life with turnover intention among the nurses of public and private hospitals in selected cities of Guilan province, Iran, in 2016. J Health Res Commun 2017; 3(3): 12-24. [Persian].

- de Oliveira DR, Griep RH, Portela LF, Rotenberg L. Intention to leave profession, psychosocial environment and self-rated health among registered nurses from large hospitals in Brazil: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2017; 17(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1949-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chênevert D, Jourdain G, Vandenberghe C. The role of high-involvement work practices and professional self-image in nursing recruits’ turnover: a three-year prospective study. Int J Nurs Stud 2016; 53:73-84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.09.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lo WY, Chien LY, Hwang FM, Huang N, Chiou ST. From job stress to intention to leave among hospital nurses: a structural equation modelling approach. J Adv Nurs 2018; 74(3):677-88. doi: 10.1111/jan.13481 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Alshutwi S. The influence of supervisor support on nurses’ turnover intention. Health Syst Policy Res 2017; 4(2):1-6. doi: 10.21767/2254-9137.100075 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hariri GR, Yaghmaei F, Zagheri Tafreshi M, Shakeri N. Assessment of some factors related to leave in nurses and their demographic character in educational hospitals of Shahid Behesthi University of Medical Sciences. Journal of Health Promotion Management 2012; 1(3): 17-27. [Persian].

- Takase M. A concept analysis of turnover intention: implications for nursing management. Collegian 2010; 17(1):3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2009.05.001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rodgers BL, Knafl KA. Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2000.

- Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2005. p. 63-76.

- Schwartz-Barcott D, Suzie Kim H. An expansion and elaboration of the hybrid model of concept development. Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. Saunders; 2000. p. 129-59.

- Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med 2019; 7:2050312118822927. doi: 10.1177/2050312118822927 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004; 24(2):105-12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Guba EG. Fourth Generation Evaluation. 1st ed. United Kingdom: SAGE Publications; 1990.

- Pizam A, Thornburg SW. Absenteeism and voluntary turnover in Central Florida hotels: a pilot study. Int J Hosp Manag 2000; 19(2):211-7. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4319(00)00011-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cho YJ, Lewis GB. Turnover intention and turnover behavior: implications for retaining federal employees. Rev Public Pers Adm 2012; 32(1):4-23. doi: 10.1177/0734371x11408701 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sager JK, Griffeth RW, Hom PW. A comparison of structural models representing turnover cognitions. J Vocat Behav 1998; 53(2):254-73. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1997.1617 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Linares PJ. Job Satisfaction, Organization Commitment, Occupational Commitment, Turnover Intent and Leadership Style of Tissue Bank Employees. Capella University; 2011.

- Kerr VO. Influence of Perceived Organizational Support, Organizational Commitment, and Professional Commitment on Turnover Intentions of Healthcare Professionals in Jamaica. Nova Southeastern University; 2005.

- Sousa-Poza A, Henneberger F. Analyzing job mobility with job turnover intentions: an international comparative study. J Econ Issues 2004; 38(1):113-37. doi: 10.1080/00213624.2004.11506667 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- DeConinck JB, Stilwell CD. Incorporating organizational justice, role states, pay satisfaction and supervisor satisfaction in a model of turnover intentions. J Bus Res 2004; 57(3):225-31. doi: 10.1016/s0148-2963(02)00289-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gaertner S. Structural determinants of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in turnover models. Hum Resour Manag Rev 1999; 9(4):479-93. doi: 10.1016/s1053-4822(99)00030-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mitchell TR, Holtom BC, Lee TW, Sablynski CJ, Erez M. Why people stay: using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Acad Manage J 2001; 44(6):1102-21. doi: 10.5465/3069391 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Maertz CP Jr, Griffeth RW. Eight motivational forces and voluntary turnover: a theoretical synthesis with implications for research. J Manage 2004; 30(5):667-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jm.2004.04.001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Leineweber C, Chungkham HS, Lindqvist R, Westerlund H, Runesdotter S, Smeds Alenius L. Nurses’ practice environment and satisfaction with schedule flexibility is related to intention to leave due to dissatisfaction: a multi-country, multilevel study. Int J Nurs Stud 2016; 58:47-58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.02.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hoseini-Esfidarjani SS, Negarandeh R, Janani L, Mohammadnejad E, Ghasemi E. The intention to turnover and its relationship with healthy work environment among nursing staff. Hayat 2018; 23(4): 318-31. [Persian].

- Khajehmahmood F, Mahmoudirad G. Survey tendency to leave service and its related some factors among nurses in Zabol university hospitals. J Clin Nurs Midwifery 2017; 6(1): 73-83. [Persian].

- Andresen IH, Hansen T, Grov EK. Norwegian nurses’ quality of life, job satisfaction, as well as intention to change jobs. Nord J Nurs Res 2017; 37(2):90-9. doi: 10.1177/2057158516676429 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Zhao S, Shi L, Zhang Z, Liu X, Li L. Workplace violence, job satisfaction, burnout, perceived organisational support and their effects on turnover intention among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018; 8(6):e019525. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019525 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hesam M, Asayesh H, Roohi G, Shariati A, Nasiry H. Assessing the relationship between nurses’ quality of work life and their intention to leave the nursing profession. Quarterly Journal of Nersing Management 2012; 1(3): 28-36. [Persian].

- Rozo JA, Olson DM, Thu HS, Stutzman SE. Situational factors associated with burnout among emergency department nurses. Workplace Health Saf 2017; 65(6):262-5. doi: 10.1177/2165079917705669 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Arslan Yurumezoglu H, Kocaman G. Predictors of nurses’ intentions to leave the organisation and the profession in Turkey. J Nurs Manag 2016; 24(2):235-43. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12305 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dalvi Esfahan MR, Ganji-Arjenaki M. The impact of ethical leadership on job stress and occupation turnover intention in nurses of hospitals affiliated to Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci 2014; 16(1): 121-8. [Persian].

- Alhamwan M, Mat NB, Al Muala I. The impact of organizational factors on nurses turnover intention behavior at public hospitals in Jordan: how does leadership, career advancement and pay-level influence the turnover intention behavior among nurses. Journal of Management and Sustainability 2015; 5(2):154. doi: 10.5539/jms.v5n2p154 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Modau FD, Dhanpat N, Lugisani P, Mabojane R, Phiri M. Exploring employee retention and intention to leave within a call centre. SA J Hum Resour Manag 2018; 16(1):1-13. doi: 10.4102/sajhrm.v16i0.905 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cowden T, Cummings G, Profetto-McGrath J. Leadership practices and staff nurses’ intent to stay: a systematic review. J Nurs Manag 2011; 19(4):461-77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01209.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Sewell KA, Woody G, Rose MA. The state of the science of nurse work environments in the United States: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Sci 2018; 5(3):287-300. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.04.010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nasabi NA, Bastani P. The effect of quality of work life and job control on organizational indifference and turnover intention of nurses: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Cent Eur J Nurs Midwifery 2018; 9(4):915-23. doi: 10.15452/cejnm.2018.09.0024 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Inoue T, Harada H, Oike M. Job control, work-family balance and nurses’ intention to leave their profession and organization: a comparative cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2016; 64:52-62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.09.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zadi Akhule O, Nasiri Formi E, Lotfi M, Memarbashi E, Jafari K. The relationship between occupational hazards and intention to leave the profession among perioperative and anesthesia nurses. Nurs Midwifery J 2020; 18(7):532-42. doi: 10.29252/unmf.18.7.532 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jacobs E, Roodt G. Organisational culture of hospitals to predict turnover intentions of professional nurses: research. Health SA Gesondheid 2008; 13(1):63-78. doi: 10.10520/ejc35035 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Liou SR, Grobe SJ. Liou SR, Grobe SJPerception of practice environment, organizational commitment, and intention to leave among Asian nurses working in UShospitals. J Nurses Staff Dev 2008; 24(6):276-82. doi: 10.1097/01.NND.0000342235.12871.ba [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L, Van den Heede K, Griffiths P, Busse R. Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet 2014; 383(9931):1824-30. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62631-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Galletta M, Portoghese I, Carta MG, D’Aloja E, Campagna M. The effect of nurse-physician collaboration on job satisfaction, team commitment, and turnover intention in nurses. Res Nurs Health 2016; 39(5):375-85. doi: 10.1002/nur.21733 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Klein D. The Effect of Hospital Nurse Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction on Turnover Intention and Compassion Fatigue [dissertation]. Walden University; 2017.

- Liou SR. Nurses’ intention to leave: critically analyse the theory of reasoned action and organizational commitment model. J Nurs Manag 2009; 17(1):92-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00873.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau AE, Cummings G, Cranley LA, Ferron EM, Harvey S. Determinants of hospital nurse intention to remain employed: broadening our understanding. J Adv Nurs 2010; 66(1):22-32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05190.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vardaman JM, Taylor SG, Allen DG, Gondo MB, Amis JM. Translating intentions to behavior: the interaction of network structure and behavioral intentions in understanding employee turnover. Organ Sci 2015; 26(4):1177-91. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2015.0982 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980.

- Camerino D, Conway PM, van der Heijden BI, Estryn-Béhar M, Costa G, Hasselhorn HM. Age-dependent relationships between work ability, thinking of quitting the job, and actual leaving among Italian nurses: a longitudinal study. Int J Nurs Stud 2008; 45(11):1645-59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.03.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Flinkman M, Isopahkala-Bouret U, Salanterä S. Young registered nurses’ intention to leave the profession and professional turnover in early career: a qualitative case study. ISRN Nurs 2013; 2013:916061. doi: 10.1155/2013/916061 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Soudagar S, Rambod M, Beheshtipoor N. Intention to stay at nursing profession and its related factors. Sadra Med Sci J 2014; 2(2):185-94. [ Google Scholar]

- Felps W, Mitchell TR, Hekman DR, Lee TW, Holtom BC, Harman WS. Turnover contagion: how coworkers’ job embeddedness and job search behaviors influence quitting. Acad Manage J 2009; 52(3):545-61. doi: 10.5465/amj.2009.41331075 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Barrick MR, Mount MK. Effects of impression management and self-deception on the predictive validity of personality constructs. J Appl Psychol 1996; 81(3):261-72. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.81.3.261 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shokri Nagharloo F, Soloukdar A. Impact of motivational factors on job retention and loyalty of hospital nurses. Iran J Nurs Res 2018; 12(6):73-8. doi: 10.21859/ijnr-120610 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Brunetto Y, Rodwell J, Shacklock K, Farr-Wharton R, Demir D. The impact of individual and organizational resources on nurse outcomes and intent to quit. J Adv Nurs 2016; 72(12):3093-103. doi: 10.1111/jan.13081 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mosadeghrad AM, Ferlie E, Rosenberg D. A study of the relationship between job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intention among hospital employees. Health Serv Manage Res 2008; 21(4):211-27. doi: 10.1258/hsmr.2007.007015 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nabizadeh Gharghozar Z, Atashzadeh Shoorideh F, Khazaei N, Alavi-Majd H. Assessing organizational commitment in clinical nurses. Quarterly Journal of Nersing Management 2013; 2(2): 41-8. [Persian].