Journal of Caring Sciences. 13(3):148-157.

doi: 10.34172/jcs.33578

Original Article

Early Palliative Care in the Emergency Department: A Concept Clarification

Kelly Counts Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1, *

Sue Lasiter Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, 1

Author information:

1School of Nursing & Health Studies, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, MO, United States

Abstract

Introduction:

Healthcare advances have contributed to patients living longer with chronic illnesses and diseases with uncertain trajectories impacting quality of life (QOL). Palliative care (PC) is no longer only for dying oncology patients as many healthcare practitioners have adopted the PC concept in diverse care settings and the timing of PC implementation remains ambiguous. There is a need to develop an operational definition of early palliative care (EPC) by clarifying the phenomenon and bridging concepts with empirical data to develop and test possible interventions before integrating EPC into emergency care (EC).

Methods:

Norris’ concept clarification method was used as the philosophical framework to define, analyze, and clarify EPC. An electronic search of literature from 2000-2024, using CINAHL, PubMed, APA PsychINFO, and Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection databases and search terms "early palliative care" AND "emergency care" NOT "animals", and NOT "pediatrics" were screened for eligible articles.

Results:

Of the 826 articles identified; 22 articles were retained for review. Attributes included timing, palliative, and EC; antecedents included symptom burden, access to care, and cognitive awareness; consequences included QOL and resource utilization; an empirical referent used to screen patients is the highly accurate surprise question "Would I be surprised if this patient died within a year?"

Conclusion:

Clarifying the concept of EPC leading to an operational definition will advance the development of interventions that support the implementation of EPC in ED clinical practice.

Keywords: Early palliative care, Emergency care, Quality of life, Chronic disease, Concept analysis, Concept clarification

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Author(s).

This work is published by Journal of Caring Sciences as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Funding Statement

No financial or grant support was received for this concept clarification publication.

Introduction

Palliative care (PC) aims to improve quality of life (QOL) through an interdisciplinary, holistic care approach that can be used to improve everyday life for patients with chronic illnesses and poor prognostication of illness trajectory. Additionally, PC can reduce system demand or burden to the provision of emergency care (EC).1,2 There is a need to develop an operational definition of early palliative care (EPC) by clarifying the phenomenon and bridging concepts with empirical data to develop and test possible interventions before integrating EPC into EC.

The roots of PC started in hospice care, but the scope of PC has evolved over the last decade and is no longer identified solely for oncology patients who are dying. PC was first explored in 1967 as a concept in the United Kingdom by Cicely Saunders then in 1974, introduced in the United States.3,4 Since then, the concept of PC has been studied by various health disciplines in many care settings and is a relatively new concept for practitioners in the EC subspecialty.3

By the year 2030, 20% of the United States population is forecasted to live beyond 65 years of age, and adults over 85 are expected to exceed 9 million.5-7Thus, many aging adults will live with chronic, life-limiting diseases, making PC a health priority. Furthermore, QOL should be prioritized alongside disease treatments, allowing patients to live fully through implementation of PC benefits.5,6Limitations to implementing PC are mainly due to ambiguity of the concept, lack of resource availability, poor prognostication of illness trajectory, unfavorable outcomes due to delayed implementation, and lack of health literacy among providers and patients.7-10 These barriers remain despite the large volume of published literature supporting the emerging field of PC.11

While PC is currently recognized for its application in patients who access emergency department (ED) care for chronic and life-limiting illnesses, the timing of PC implementation remains unclearly defined.12-15 Experts have identified that implementation of PC should occur well before the end-of-life and optimally when a life-limiting disease diagnosis is made.15Thus, timing is key to the contribution PC offers regarding QOL of patients with chronic, life-limiting illnesses and should be implemented early in the treatment plan for those with a newly diagnosed chronic illness however, less than 14% of patients who would benefit from EPC actually receive EPC resources.10,11

Clarification of the concept of EPC would support the development of an operational definition to guide providers in the EC setting and for researchers who wish to test interventions for early implementation of PC. A focus on EPC would subsequently improve QOL and minimize symptom burden for patients with an uncertain disease trajectory. Thus, this concept clarification aimed to define the term early as it relates to PC and to clarify EPC terminology. The goal is to aid in the development and implementation of EPC for clinical practice and to support ongoing EPC research in the ED.

Norris Methodology

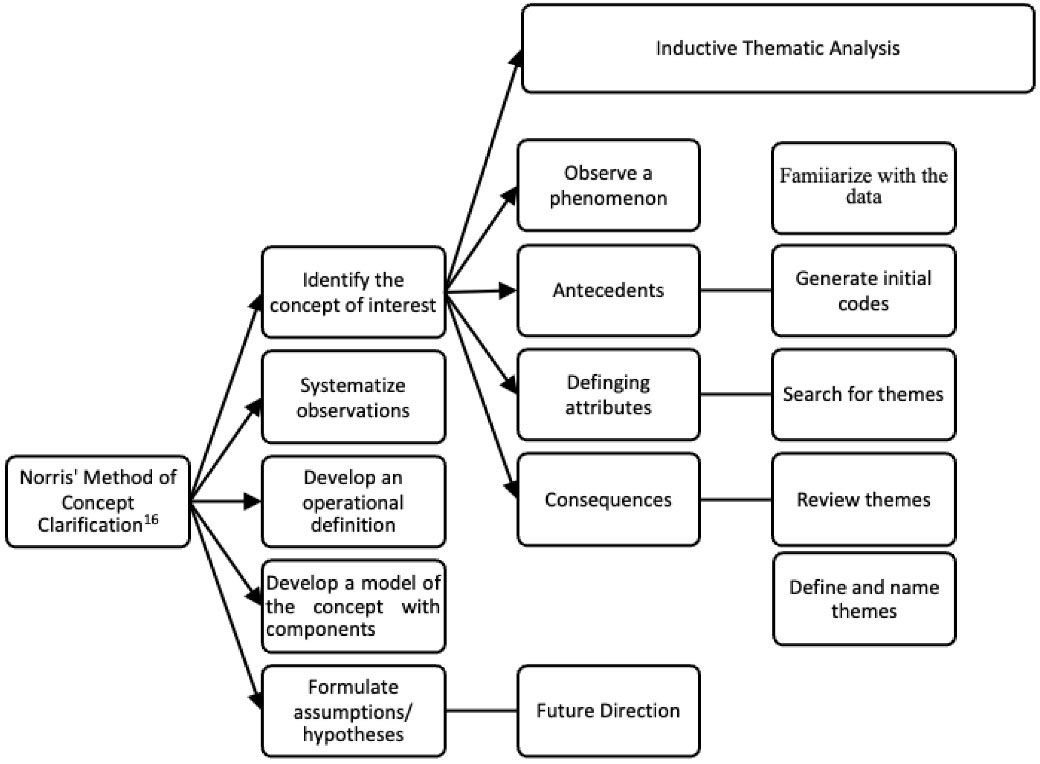

Norris’ (1982) concept clarification framework (See Figure 1) was used for its philosophical underpinnings to define, analyze, and clarify concepts such as EPC.16,17Norris’s method was selected for this concept clarification to thematically review and synthesize literature and guide the development of the EPC concept clarification. The steps for concept clarification follow: (a) select the concept or phenomenon and observe and describe the phenomenon used by other disciplines; (b) synthesize the observations and descriptions; (c) propose an operational definition and contextual application for the concept; (d) develop a conceptual model; and (e) formulate a conceptual hypothesis.16,17See Figure 1 for Norris’ concept clarification framework.

Figure 1.

Concept clarification in nursing

.

Concept clarification in nursing

Concept clarification strategies have been adapted from conceptual analysis by aiming to operationalize a concept. A concept analysis differs from a concept clarification by defining a concept’s attributes and semantic structures.16,17

Materials and Methods

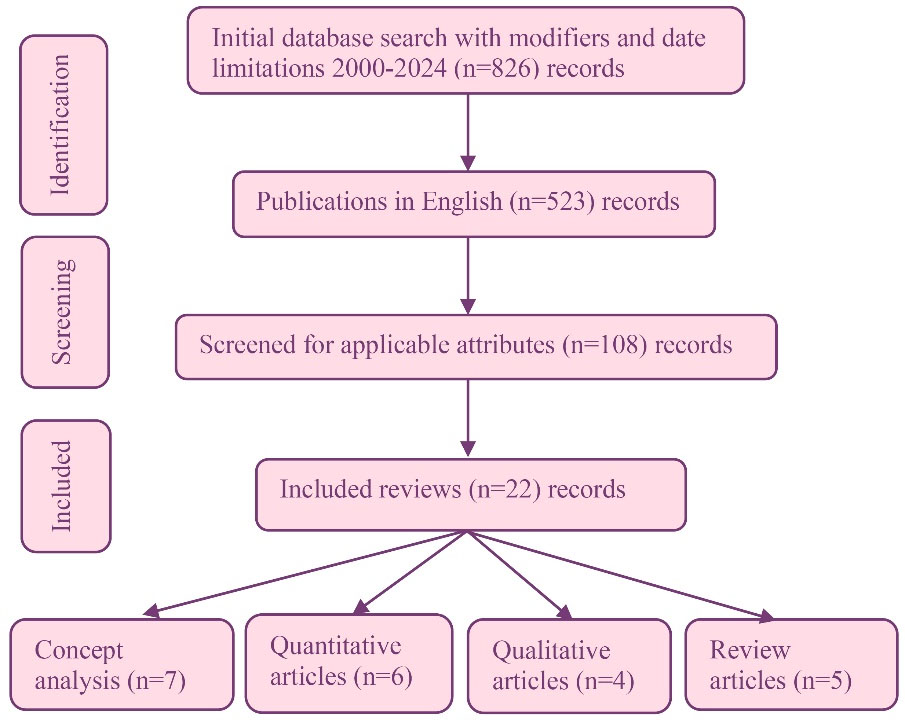

As a first step in concept clarification, the concept of early palliative care was explored. A search was conducted using the databases PubMed, CIHAHL, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, and PsychINFO for articles published in peer-reviewed journals using the following search terms “early palliative care” AND “emergency care” AND “emergency department,” NOT “end of life,” NOT “pediatric,” NOT “children,” NOT “adolescents,” NOT “dogs,” NOT “cats,” NOT “horse, or “NOT” animals. This search returned 826 articles that met inclusion criteria: published in English, published between 2000 and 2024 (advances in PC publications occurred during this time frame), and had a medical, nursing, or psychology emphasis. We did not include editorials, commentaries, book reviews, or anonymous documents. After duplicates were removed and titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, 108 articles were retained for evaluation. The first author conducted a full-text thematic analysis to identify attributes related to EC and PC specific to EPC, EC, and QOL. Twenty-two articles contained attributes and were retained for use in concept clarification (See Table 1). A flow chart of the article selection process is demonstrated in Figure 2. There is no Equator Network reporting guideline for a concept clarification, but the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was adapted.18

Table 1.

able of articles selected for concept clarification

|

Author & Year

|

Study design

|

Key theme

|

Exemplary quotation

|

Study findings

|

| Guo et al (2012)1 |

Concept analysis |

PC |

“The antecedents, attributes and consequences of palliative care are more up to date from previous concept analysis” |

An evolutionary concept of PC to provide the most up to date and most effective ways to provide PC. |

| Sue-A-Quan et al (2023)2 |

Qualitative research |

Provider perceptions of EPC |

Questions about barriers and benefits defined “early” as 6-24 months before the death of the patient. |

A PC physicians’ perception of conditions required to provide EPC survey identified four themes limiting EPC. The barriers include a) clear delineation of roles as a provider, b) shared care among various providers, c) adequate resources to provide PC, and d) addressing the misconception that PC equals end of life |

| Bayuo et al (2022)3 |

Review article |

PC interventions, ED, delivery models |

PC interventions implemented in the ED. |

PC interventions in the ED were categorized (a) screening, (b) goals of care discussions, (c) symptom management including pain and distressing symptoms, (d) transitions of care, (e) end of life care, (f) family/caregiver support, and (g) ED staff education. |

| Huo et al (2019)7 |

Quantitative study |

PC,

knowledge |

Knowledge of PC among Americans is low. |

71% had no knowledge of PC. Comparative age groups resulted those 65 years and older had the best knowledge; female gender more knowledgeable than male |

| Akoo and McMillan (2023)9 |

Evolutionary concept analysis |

Ambiguity of the concept PC |

Misunderstanding perpetuates negative impressions of PC and identified as a barrier |

Clarification of negative impressions and barriers |

| Hausner et al (2021)10 |

RCT |

Timing was defined as referral to death; early > 12 months, intermediate > six to 12 months, and late < six months from referral to death. |

Earlier referral to outpatient oncology patients and defining timing for early |

Evidence supports EPC referral in the advanced cancer population and positively impacts QOL. |

| Meghani (2004)13 |

Concept analysis |

PC |

“New models of palliative care will rest upon the commitment of health professionals to recognize and integrate the changing concept of palliative care into everyday practice” |

The purpose was to evaluate the evolution of concepts related to PC. |

| Taber et al (2019)14 |

Quantitative

study |

PC beliefs and knowledge |

“A need exists to improve the awareness and attitudes of the general public about palliative care.” |

Surveys to assess the knowledge and beliefs among the general population |

| Wang (2017)15 |

Meta-analysis |

PC, ED |

None |

The review article summarizes the phenomenon of PC initiation in the ED. |

| Nadolny et al (2023)19 |

Scoping review |

EPC intervention |

EPC is a complex intervention with encompasses multiple treatment modalities, each unique to the diagnosis. |

Study screened for elements of EPC and elicited several barriers with most reported ambiguity of when to initiate PC referencing lack of consensus defining timing. |

| Callaway (2012)20 |

Review article |

PC consult, nurse practitioner |

Initiating PC at time of chronic disease diagnosis. |

Scientific literature searched including www.palimed.org for practice standard guidelines. |

| Davis et al (2019)21 |

Concept analysis |

EC |

“Emergency care attributes contribute to body of knowledge and clarifies the ambiguity of practice for emergency nurse practitioner (ENP)” |

Defining attributes include immediate evaluation, treatment of unexpected injury/illness and delivery of care and scope of practice for the ENP |

| Applequist and Daly (2015)22 |

Concept analysis |

Palliation |

“Palliation best described to relieve symptoms, relieve suffering, and improve quality of life.” |

Three attributes are (a) patient goal-directed symptom relief, (b) interpersonal human presence, and (c) non curative intervention. |

| Kirkpatrick et al (2017)23 |

Concept analysis |

PC nursing |

“…all nurses must be prepared to deliver high quality palliative care upon entry into practice” |

PC nursing competence is a necessary antecedent to quality PC nursing. |

| DeVader et al (2012)24 |

Illustrative case study |

PC

ED |

Illustrative case to discuss the importance of PC in the ED |

Highlights how medical specialties can collaborate: emergency medicine and PC |

| Kistler et al (2015)25 |

RCT |

PC,

EC |

Emergency initiated PC consult |

Test the effects of PC on QOL when implemented by EC providers. |

| Reuter et al (2019)26 |

Quantitative |

EM PC intervention |

“The ED may be a key location to expand the reach of palliative care for patients with cancer” |

Utilization of 5-SPEED screening tool allowed for successful identification of patient with PC needs in the ED allowing for improved access to PC and without increasing the length of stay in the ED |

| Denney et al (2021)27 |

Pilot Project |

Early palliative consultation, ED clinical algorithm |

Early identification of patient |

Early identification of patients through the ED noted decreased length of stay in hospital, less radiographic tests, less hospital deaths and decreased overall hospital cost. |

| Hannon et al (2017)28 |

Qualitative grounded theory |

Patient experience receiving EPC |

Participants felt guided and supported through their illness by the holistic approach of EPC |

26 patients and 14 caregivers were interviewed recruited from the intervention arm of cluster RCT of EPC vs standard oncology care. Participants commented on QOL, quality of care and experiences with the PC team with an overarching positive feedback. Elements can be used to define future EPC models. |

| Wheeler (2016)29 |

Review article |

PC, nurse practitioner |

Idea is PC is part of the role for every nurse practitioner |

Introduction of tools for symptom management, starting a difficult conversation, discussing impact on quality of life and refer when needed |

| Wantonoro et al (2022)30 |

Concept analysis review |

Descriptions of preceding events, timing of PC implementation, and outcomes of patient receiving PC |

Use of terms, critique of four existing PC concept analysis |

Confirmation of approach to alleviating symptoms, improved patient and caregivers QOL, and ensuring knowledge in the clinical practice setting. |

| Mierendorf and Gidvani (2014)31 |

Review article |

PC, ED |

Patients living with chronic diseases and illness seek EC for symptom relief. |

Identification of patients who need palliation, discussing prognosis, initiating the referral for PC in the EC setting. |

Abbreviations: QOL, quality of life; PC, Palliative care; EC, emergency care; EPC, early palliative care; ED, emergency department.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of literature search

.

Flow chart of literature search

Concept or Phenomenon of Early Palliative Care

EPC is an umbrella term that needs more conceptual clarity under a wide range of disciplinary definitions. The phenomenon of EPC has been referenced as a complex treatment intervention with multiple treatment modalities available that can be implemented at various times with varied outcomes.19 These interventions positively impact a range of patient outcomes, including QOL, by implementing resources such as music, art, and animal therapy; assistance with transportation, meal preparation, and pain/medication management; and physical and occupational therapy.32The need for more consensus regarding the best time to implement EPC has emerged. It is based on an uncertain disease trajectory, unawareness of positive impacts, resource availability, and utilization of targeted interventions.3EPC delivers a holistic approach compatible with the philosophical underpinnings of EC scope of practice. Timing of implementation for patients with chronic disease is fundamental to improving QOL.10,20,33Clarifying the concept of EPC will facilitate consistent understanding of the concept, allow opportunity to improve QOL, resulting in better utilization and integration of PC for patients who seek EC for chronic illness symptom burden relief.

Observations and descriptions

Antecedents

Antecedents are events or incidents that must be in place before attributes can formulate a concept and should be considered from the patient’s point of view.17 Antecedents include precipitating event-symptom burden, access to care, and cognitive awareness.

Precipitating Event-Symptom Burden

A precipitating event is equivalent to a symptom burden. Patients who have an acute undiagnosed illness or chronic disease seek EC for symptom burden relief. Symptom burden was defined in a concept analysis as “subjective, quantifiable prevalence, frequency, severity of symptoms placing a physiological burden on patients producing multiple negative physical and emotional patient responses”.34One of the three most common complaints of symptom burden includes anxiety, shortness of breath, and pain.5,35-37

Access to Care

Access to care can be a limiting factor as a recognized antecedent. Does the patient have access to care, including means of transportation, physical capacity to participate in the PC referral benefits, and cognitive awareness of the benefits and positive impacts on QOL?

Cognitive Awareness

Cognitive awareness is not only limited to patients but can include the knowledge and beliefs of the EC team. The cognitive awareness of PC for adults in the United States is deficient.7,32,38-40 In a quantitative study by Huo et al, a survey revealed that 71% of adults had no knowledge of PC, and common misconceptions existed.7The most common misconception about PC is that it is only implemented when hospice care or end-of-life care is needed, not realizing that ongoing, symptom treatment can still be delivered.7,9,14,38-40Practitioners perpetuate this misperception with the continued use of the “surprise question.”

Attributes

The hallmark of attributes is defining the characteristics of a concept. The attributes were inductively identified from the search and synthesis of literature based on keywords. Common themes were extrapolated, and the similarity of the attributes contributed to the development of a concept definition.16 The three attributes identified included (a) introduction of care-timing, (b) palliative, and (c) EC.

Introduction to Care-Timing

The timing of introduction to care is defined as when a patient seeks EC for symptom burden relief. It is not related to the time of day but rather timing, which refers to the time of diagnosis. Guo et al recommend implementing PC at the time of initial diagnosis to optimize QOL for the patient.1Accordingly, Callaway emphasized that timing is everything.20 Benefits of PC need to occur when a chronic illness or disease is diagnosed, eliminating delays in effective pain management, and promoting overall QOL. The PaCES Project defined EPC as < 90 days before death; however, hospice is described as death within 90 days.41Hausner et al defined the timing of PC referral as it related to death: early > 12 months, intermediate > 6 to 12 months, and late < 6 months from referral to death.10Early identification of patients needing PC is the first step in developing EPC concept clarification.

Palliative

The second attribute is palliative. Palliative is defined as improving QOL through a psychological, physiological, emotional, and spiritual holistic approach for patients, families, and caregivers.14,15,32,35PC is an ever-changing dynamic concept that describes actions that meet patients’ needs and impacts QOL.1,13Applequist and Daly defined palliative as goal-directed actions to relieve symptoms from noncurative interventions.22PC in the discipline of nursing is defined by Kirkpatrick et al as a holistic care aimed at improving QOL using a personalized, interprofessional approach.23

Emergency Care

The last attribute is EC. The origin of EC predates modern healthcare, providing the venue for centuries to care for war victims with acute injuries.21,24Modern EC includes both settings and providers who perform rapid assessments and deliver acute and resuscitative treatments and is often the entry point for access to health care services.3,21The ED setting is the intersection of high volume and high patient acuity where practitioners from varied disciplines evaluate and treat emergent and urgent health issues resulting in the development of practice guidelines for emergency based PC.42 According to Davis et al an EC concept analysis defined EC as the immediate evaluation and treatment of an unexpected injury or illness and pointed out a non-specific setting or location as a limitation.21 The overarching definition encompasses the entire EC team providing urgent, emergent, and societal needs of the population it serves.21Wang indicated that an EC setting for PC was a “win-win” for both the patient and the health care system because patients benefited from a team approach when attempting to improve QOL with early implementation of PC services.15,21,24,42 In early efforts to validate the effects of EPC, Kistler et al conducted one of the first randomized control trials to assess EPC referral in the ED targeting oncology patients with advanced, incurable cancer.25The study results revealed a low EPC rate, supporting the need for clarification of this concept. As the need for concept clarification for EPC has been identified, further research efforts have been fostered to identify the limiting components, delivery models, and outcomes associated with PC implementation in the EC setting.

Empirical Referents

Empirical referents operationalize the defining attributes to develop a measurable concept.43The empirical referents result from validated prognostic screening tools, EC-based practice guidelines, and QOL surveys emphasizing a holistic care approach.42,44 An example of an empirical referent used to screen patients who would benefit EPC is the highly accurate surprise question “Would I be surprised if this patient died within a year?”44-47 The perception of physical symptoms, clinical expertise, and collaboration with early PC experts will be the defining terms for this concept clarification.25,44

In a cross-sectional descriptive study by Reuter et al an ED-based PC intervention program aimed to assess the feasibility of identifying cancer patients with unmet PC needs.26 Historically, ED research has emphasized how to expedite a PC consultation rather than identify the immediate needs.26 The screen for palliative and end-of-life care needs in the ED (SPEED) survey was the first ED-based tool to focus on PC topics such as pain management, home care resources, medication management, psychological support, and goals of care.26 The 5-SPEED assessment is scored using a ten-point Likert scale, and if patients scored positive, an automatic pharmacy and social worker consultation were generated. A total of 1278 patients over seven months were screened in the ED. Of the 817 patients who completed the 5-SPEED tool, 50% of cancer patients were identified as having unmet PC needs, and these needs were immediately addressed while in the ED.26

Of recent, a pilot project was conducted to determine measurable effects of an ED clinical algorithm to increase EPC consultation sponsored by “Choosing Wisely Campaign” supported by the American College of Emergency Physicians.27 Strategic pathways were piloted to assist ED providers on how to best use PC services in the ED setting. The pilot project enrolled 662 patients identifying under-recognized patient population that would downstream benefit PC by decreased length of stays resulting in lower overall hospital costs, fewer surgical and diagnostic procedures, and improve QOL vs “quantity of life.” 27

In a study by de Nooijer et al the goal was to evaluate the timing of PC implementation delivery for older adults with complex care needs, including those with impaired cognition, by using a FRAILTY + (PC intervention initiated by a PC nurse) intervention according to prescribed criteria.36The study outcomes resulted in identifying individual needs and core components that benefited from PC intervention. Studies like this one screening patients and evaluating screening tools and interventions based on symptoms are necessary to benefit the patients with EPC needs further.

Consequences

Consequences are a result of an occurrence of a developed concept. A concept is enacted when the consequences work together.16,24,43The positive consequences of EPC include QOL, resource availability and access, and health literacy. QOL is improved for patients who seek EC for symptom burden relief, and EPC implementation occurs due to these attributes.32,33 The introduction of care-timing, palliative, and EC have all been defined as a common thread in the literature, resulting in positive consequences that promote health literacy, resource utilization, and cognitive awareness.3,20,21,27,48 The consequences trigger the ED care team to discuss patients’ goals of care.

Resource utilization is a positive consequence of EPC. Examples of patient-focused PC that impact QOL include advanced care planning (ACP), shared goals of care conversations, how to have difficult conversations, pain management, pet therapy, music therapy, art therapy, chore worker assistance, meals on wheels, and transportation.32

Unfortunately, barriers exist as negative consequences to concept clarification. Resource unavailability is one of the barriers identified in the synthesis of literature.7,19,26,42 Unavailable resources include a provider who lacks knowledge and awareness of PC and neglects consistent consultation or referral patterns.49 The patient’s access to resources and ability to follow through with PC is frequently discussed in the literature as a limitation.

The timing of PC is both an antecedent and a consequence. Several models have attempted to reach clarity on EPC through research. Care models and screening tools have been developed and utilized to bridge this identified gap in care. Hannon et al describe an EPC model as integrated into the standard of care early in a patient’s illness trajectory until a patient requires inpatient PC services.28 The ED setting can be the crossroads for high volume, high patient acuity used to evaluate and treat emergent and urgent care issues which can be perceived as an antecedent and consequence to barriers.28,35,42

Operational Definition

‘What does EPC mean in EC?” An operational definition for EPC and its application in EC is supported by the antecedents, attributes, empirical referents, and consequences described in Table 2.Based on a multidisciplinary literature review, we define EPC as “a treatment intervention implemented at the time a life-threatening illness or chronic disease with a poor prognostication trajectory is diagnosed or discovered to improve or maintain QOL.” The attributes include cognitive awareness, desire to help others as one’s purpose in life, family conference, PC, and early disease trajectory. The consequences include QOL, resource utilization, spiritual dimensions, health literacy, disease trajectory, meaningful work, holistic care, ACP, and goals of care.21,22,25,28,29,50 This definition further supports the well-published PC conceptual analyses1,13,23,24,30 and WHO definition; EPC improves QOL for patients and families through a holistic physiological, psychological, spiritual, and social focus.35

Table 2.

Antecedents/Attributes/Empirical Referents/Consequences

|

Antecedents

|

Defining attributes

|

Empirical referents

|

Consequences

|

|

Emergency care

|

| Access to care |

Immediate evaluation of complaints |

Triage based on Emergency Severity Index |

Resource management for care based on symptoms |

| Adaptable |

Unexpected complaints |

Unpredicted onset |

Predictable, patient focused outcomes with improved QOL |

| Precipitating events |

Life limiting/threatening |

QOL impacted |

Symptom burden relief |

| Screening |

ED care providers |

EC provided at multiple levels |

Engagement of patients with a diagnosis of chronic disease with improved health literacy |

| Assessment |

Exacerbation of symptoms from undiagnosed chronic disease |

Symptom burden to include but not limited to pain, shortness of breath, confusion, anxiety, fear |

Disease trajectory to positively impacting QOL |

|

Early palliative care

|

| Access to care |

Holistic care |

Provide physiological, psychological, emotional, and spiritual care |

Improve QOL |

| Precipitating events |

Symptom burden relief |

Shortness of breath, pain, anxiety |

Minimize symptoms to improve QOL |

| Cognitive awareness |

Integrating knowledge |

Increase appropriate utilization of PC services when appropriate |

Health literacy related to terminology and benefits |

| Resource utilization |

Engaging care of services |

Nursing specific based on values and scope of practice |

Implement patient focused PC needs to positively impact QOL such as ACP, pain management, pet therapy, music therapy, art therapy, chore worker assistance, meals on wheels, and transportation |

Abbreviations: QOL, quality of life; ED, emergency department; ACP, advanced care planning.

Model

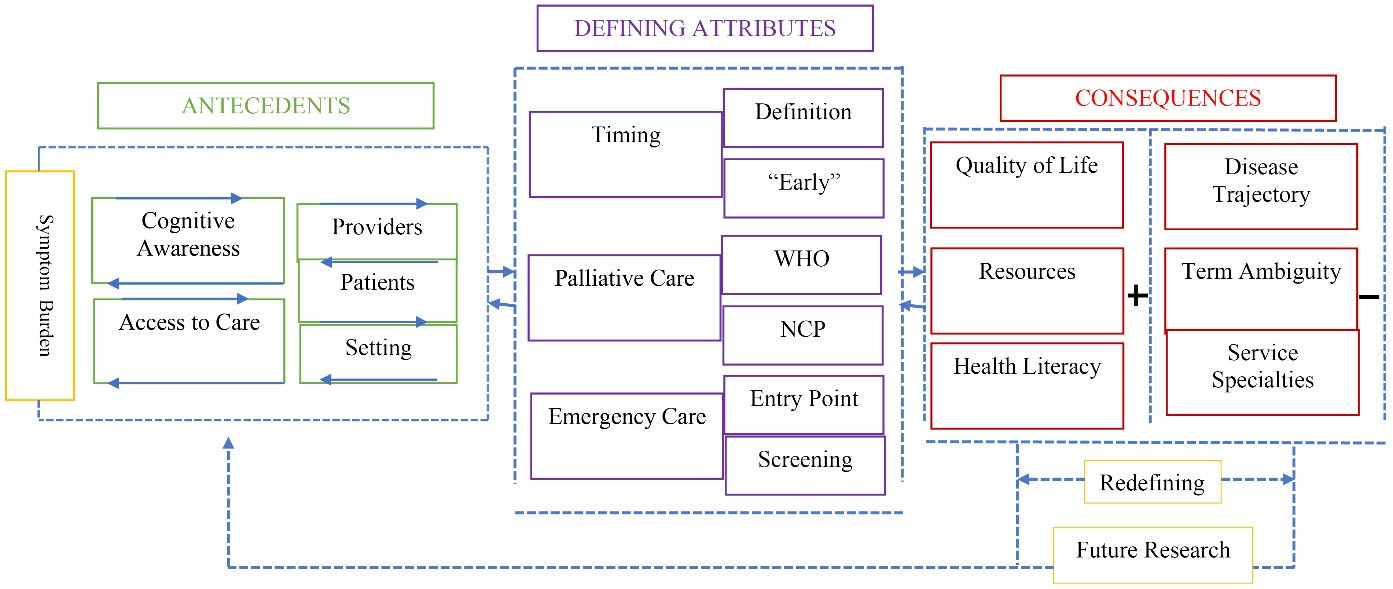

Norris’ approach to concept clarification was to develop an operational modell6,17 (see Figure 1). The EPC model is displayed in Figure 3, outlining existing themes from the state of the science literature, and compares EPC and EC. The operational model (Figure 3) demonstrates the flow and alliances among the attributes, antecedents, consequences, and empirical referents. The figure delineates the reliance on each component to make the model successful while recognizing how barriers can limit the concept by delaying EPC and thereby negatively impacting QOL. Ongoing research that tests EPC is compatible with curative treatment and should be delivered based on need and symptom burden rather than prognosis.

Figure 3.

Early Palliative Care Concept Clarification Model. Note: WHO, World Health Organization35; NCP, National Coalition of Palliative Care32

.

Early Palliative Care Concept Clarification Model. Note: WHO, World Health Organization35; NCP, National Coalition of Palliative Care32

Hypothesis Formulation for Early Palliative Care

Hypothesis about EPC was derived from its operational definition and model (Figure 3). We hypothesize that implementing EPC intervention in the ED will improve QOL and decrease symptom burden. Patients of any age with chronic or life-limiting diseases will have access to EPC to improve QOL by allowing full access to PC resources. Patients receiving EPC will have fewer EC visits, fewer hospitalizations and re-admissions, and lower overall care costs with an improved QOL. EPC research using a clear conceptual understanding will challenge this hypothesis, strengthen the EPC model, and evolve into a standard of care for chronically ill patients receiving EC.

Antecedents are events or incidents that must be in place before attributes can formulate a concept and should be considered from the patient’s point of view. The hallmark of attributes is defining the characteristics of a concept. Consequences are a result of an occurrence of a developed concept. When the consequences all work together, a concept will be enacted. Empirical referents operationalize the defining attributes that have been inductively coded to develop a concept. The empirical referents are resultant of holistic care approach.17,18

Discussion

In this concept clarification, we demonstrated the need and value of EPC in the EC setting. A concept clarification is essential for developing valuable and usable knowledge in nursing science.16,51Improved QOL is one of the most critical outcomes for patients, families, and caregivers.32The development of educational opportunities for providers and patients will improve EPC’s purpose, application, clarity, and value. Promoting community outreach programs and the development of academic health tools promoting the benefits of EPC can reach large populations, improve term ambiguity, and enhance resource utilization.

Concept clarification develops an operational definition of a phenomenon and bridges basic ideas or concepts with empirical data to establish or create an intervention.16,30,46,51 The goal is to construct an EC model for EPC, clarifying the benefits and value added to patients and their caregivers. Recognizing the health needs associated with patients living longer, EPC integration should be the gold standard of care, closing the gap between when patients die and how patients die.

QOL is one of the most common patient-centered outcomes identified as an EPC benefit.32,39 QOL outcomes can be easily measured by validated standardized surveys such as Medical Outcomes Study-Short Form 36 (SF-36).52 The SF-36 survey is an instrument used to evaluate QOL by measuring eight health concepts: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health perceptions, energy/fatigue levels, emotional well-being, social functioning, and vitality.52 The SF-36 survey uses a 5-point Likert scale ranging from one, equivalent to poorer (or poor) health, to five, equivalent to excellent health. Lower scores represent poorer overall health. Since the concept clarification process is inherent to its empirical referents’ validation, the SF-36 tool is a highly validated tool used to measure QOL outcomes.52 EPC concept clarification is validated by its QOL outcomes.

Resource utilization outcomes would add value to EPC’s overall benefit. A study that would critically appraise each intervention and quantify its value based on perceived or scored outcomes is additional work necessary for EPC. This opportunity could also allow for system process improvement, enhancing providers’ awareness of which intervention most positively impacts patients based on their specific chronic diseases.

The initial approach was to develop a table (see Table 2) outlining the themes from the literature further to develop equitable comparisons between emergency nursing and PC. The concept clarification model demonstrating the cohesiveness among attributes, antecedents, consequences, and empirical referents can be seen in Table 2. The model clearly delineates the reliance on each component to define EPC concept clarification while recognizing how the barriers can impede the concept’s success, ultimately negatively impacting the overall QOL for the patient who seek EC for symptom burden relief.

Closing the research gap by defining EPC will further promote the development and validation of screening tools that identify patients early in their disease trajectory that would benefit from EPC. Many screening tools have been tested,27,45but one standardized, validated tool measuring the need for EPC for EC screening does not exist in the literature. A standardized screening tool would add construct validity to the concept clarification of EPC. An innovative idea for a validated screening tool used for EPC could identify and match resources needed for individualized patients in an algorithmic pattern.

The implications of EPC will allow care providers to recognize patients who would benefit from EPC and promote an improved QOL. Enhanced cognitive awareness will limit the ambiguity of need and provide the confidence to implement a PC referral when the patient seeks EC for symptom burden relief.9,14PC focuses on relieving symptom burden by a holistic approach to promote improved QOL.1,20,24,34 A holistic care approach will be implemented based on the timing of the encounter, the need for the introduction of services, cognitive awareness from both patient and provider and management of symptoms in the context of improving QOL.

Additional limitations exist secondary to the ambiguity of the terminology.21,53 The distinction of identifying the differences between PC, hospice care, and end-of-life care is a common cognitive awareness barrier.1,6,11,21,41,54Definition discrepancies may result in delayed referrals to PC. Terminology confusion and gaps in care may also result in delayed access to care, impacting QOL for patients who seek EC for symptom burden relief.37,41,49,54Lastly, one of the biggest obstacles is provider uncertainty and unreliable identification of patients with unsure disease trajectories, delaying EPC.33 A PC providers’ perception of conditions required to provide EPC survey identified four themes limiting EPC. The barriers include (a) a clear delineation of roles as a provider, (b) shared care among various providers, (c) adequate resources to provide PC, and (d) addressing the misconception that PC equals end-of-life.2Many barriers and limitations still exist for EPC, broadening the gap in the literature and demonstrating the demand for ongoing research.

Conclusion

This concept clarification supports EPC by operationalizing the definition as a treatment intervention implemented when a life-threatening illness or chronic disease with a poor prognostication for illness trajectory is diagnosed or discovered. This concept clarification will allow EPC implementation to become a standard of care, an evidenced-based intervention to complement the existing care paths initiated by the EC team. Early PC implementation will enhance the overall QOL and minimize the symptom burden for chronically ill patients who seek EC services for relief from symptoms. This concept clarification will enhance providers’ and patients’ cognitive awareness and knowledge. Recognizing the delineation of resource-focused utilization necessary for EPC to be impactful, key stakeholders need to be identified to support further research and EPC implementation based on individuals’ needs. Concept clarification of EPC is the first step to ensuring every patient has access to EPC who seeks EC for symptom burden relief.

Acknowledgments

I sincerely appreciate the ongoing support from my Ph.D. committee member and scholar mentor, Dr. Lynn Schallom. ~ Thank You! Kelly Counts.

Competing Interests

There is no conflict of interest for authors. International Committee for Medical Journal Ethics

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest form submitted.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this concept clarification are included in this published

article.

Ethical Approval

There are no ethical issues affiliated with this submission and IRB request was not sought for this concept clarification because this was not human subjects’ research.

Funding

No financial or grant support was received for this concept clarification publication.

Research Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

What is new here?

-

A concept clarification on EPC has never been developed or published.

-

EPC is no longer only for inpatient, dying oncology patients. PC can be implemented for patients with chronic disease in care settings such as the ED at the time of a critical diagnosis.

References

- Guo Q, Jacelon CS, Marquard JL. An evolutionary concept analysis of palliative care. J Palliat Care Med 2012; 2(7):127. doi: 10.4172/2165-7386.1000127 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sue-A-Quan R, Sorensen A, Lo S, Pope A, Swami N, Rodin G. Palliative care physicians’ perceptions of conditions required to provide early palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2023; 66(2):93-101. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2023.04.008 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bayuo J, Agbeko AE, Acheampong EK, Abu-Odah H, Davids J. Palliative care interventions for adults in the emergency department: a review of components, delivery models, and outcomes. Acad Emerg Med 2022; 29(11):1357-78. doi: 10.1111/acem.14508 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Clark D. To Comfort Always: A History of Palliative Medicine Since the Nineteenth Century. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Maddocks M, Lovell N, Booth S, Man WD, Higginson IJ. Palliative care and management of troublesome symptoms for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2017; 390(10098):988-1002. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32127-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Broese JM, de Heij AH, Janssen DJ, Skora JA, Kerstjens HA, Chavannes NH. Effectiveness and implementation of palliative care interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2021; 35(3):486-502. doi: 10.1177/0269216320981294 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Huo J, Hong YR, Grewal R, Yadav S, Heller IW, Bian J, et al. Knowledge of palliative care among American adults: 2018 health information national trends survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019; 58(1): 39-47.e3. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.03.014

- Gainza-Miranda D, Sanz-Peces EM, Alonso-Babarro A, Varela-Cerdeira M, Prados-Sánchez C, Vega-Aleman G. Breaking barriers: prospective study of a cohort of advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients to describe their survival and end-of-life palliative care requirements. J Palliat Med 2019; 22(3):290-6. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0363 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Akoo C, McMillan K. An evolutionary concept analysis of palliative care in oncology care. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2023; 46(2):199-209. doi: 10.1097/ans.0000000000000444 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hausner D, Tricou C, Mathews J, Wadhwa D, Pope A, Swami N. Timing of palliative care referral before and after evidence from trials supporting early palliative care. Oncologist 2021; 26(4):332-40. doi: 10.1002/onco.13625 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira EP, Medeiros Junior P. Palliative care in pulmonary medicine. J Bras Pneumol 2020; 46(3):e20190280. doi: 10.36416/1806-3756/e20190280 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aslakson RA, Reinke LF, Cox C, Kross EK, Benzo RP, Curtis JR. Developing a research agenda for integrating palliative care into critical care and pulmonary practice to improve patient and family outcomes. J Palliat Med 2017; 20(4):329-43. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0567 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Meghani SH. A concept analysis of palliative care in the United States. J Adv Nurs 2004; 46(2):152-61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2003.02975.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Taber JM, Ellis EM, Reblin M, Ellington L, Ferrer RA. Taber JM, Ellis EM, Reblin M, Ellington L, Ferrer RAKnowledge of and beliefs about palliative care in a nationally-representative USsample. PLoS One 2019; 14(8):e0219074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219074 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wang DH. Beyond code status: palliative care begins in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2017; 69(4):437-43. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.10.027 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Norris C. Concept Clarification in Nursing. Aspen Pub; 1982.

- Rodgers B, Knafl K. Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. 2nd ed. Saunders; 2000.

- Equator Network. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist and Explanation. [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/prisma-scr/. Accessed August 2, 2024.

- Nadolny S, Schildmann E, Gaßmann ES, Schildmann J. What is an “early palliative care” intervention? A scoping review of controlled studies in oncology. Cancer Med 2023; 12(23):21335-53. doi: 10.1002/cam4.6490 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Callaway C. Timing is everything: when to consult palliative care. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2012; 24(11):633-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2012.00746.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Davis WD, Dowling Evans D, Fiebig W, Lewis CL. Emergency care: operationalizing the practice through a concept analysis. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2020; 32(5):359-66. doi: 10.1097/jxx.0000000000000229 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Applequist H, Daly BJ. Palliation: a concept analysis. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2015; 29(4):297-305. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.29.4.297 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick AJ, Cantrell MA, Smeltzer SC. A concept analysis of palliative care nursing: advancing nursing theory. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2017; 40(4):356-69. doi: 10.1097/ans.0000000000000187 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- DeVader TE, Albrecht R, Reiter M. Initiating palliative care in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2012; 43(5):803-10. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.11.035 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kistler EA, Sean Morrison R, Richardson LD, Ortiz JM, Grudzen CR. Emergency department-triggered palliative care in advanced cancer: proof of concept. Acad Emerg Med 2015; 22(2):237-9. doi: 10.1111/acem.12573 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Reuter Q, Marshall A, Zaidi H, Sista P, Powell ES, McCarthy DM. Emergency department-based palliative interventions: a novel approach to palliative care in the emergency department. J Palliat Med 2019; 22(6):649-55. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0341 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Denney CJ, Duan Y, O’Brien PB, Peach DJ, Lanier S, Lopez J. An emergency department clinical algorithm to increase early palliative care consultation: pilot project. J Palliat Med 2021; 24(12):1776-82. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0750 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hannon B, Swami N, Rodin G, Pope A, Zimmermann C. Experiences of patients and caregivers with early palliative care: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2017; 31(1):72-81. doi: 10.1177/0269216316649126 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wheeler MS. Primary palliative care for every nurse practitioner. J Nurse Pract 2016; 12(10):647-53. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2016.09.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wantonoro W, Suryaningsih EK, Anita DC, Nguyen TV. Palliative care: a concept analysis review. SAGE Open Nurs 2022; 8:23779608221117379. doi: 10.1177/23779608221117379 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mierendorf SM, Gidvani V. Palliative care in the emergency department. Perm J 2014; 18(2):77-85. doi: 10.7812/tpp/13-103 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed. Richmond, VA: National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Available from: https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp.

- Downar J, Wegier P, Tanuseputro P. Early identification of people who would benefit from a palliative approach-moving from surprise to routine. JAMA Netw Open 2019; 2(9):e1911146. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11146 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gapstur RL. Symptom burden: a concept analysis and implications for oncology nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum 2007; 34(3):673-80. doi: 10.1188/07.onf.673-680 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Palliative Care. 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/palliative-care. Accessed August 2, 2024.

- de Nooijer K, Pivodic L, Van Den Noortgate N, Pype P, Van den Block L. Timely short-term specialised palliative care service intervention for frail older people and their family carers in primary care: study protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2021; 11(1):e043663. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043663 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lowery DS, Quest TE. Emergency medicine and palliative care. Clin Geriatr Med 2015; 31(2):295-303. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2015.01.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mohammed S, Savage P, Kevork N, Swami N, Rodin G, Zimmermann C. Mohammed S, Savage P, Kevork N, Swami N, Rodin G, Zimmermann C“I’m going to push this door openYou can close it”: a qualitative study of the brokering work of oncology clinic nurses in introducing early palliative care. Palliat Med 2020; 34(2):209-18. doi: 10.1177/0269216319883980 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Center to Advanced Palliative Care. 2024. Available from https://www.capc.org/about/palliative-care/. Accessed August 2, 2024.

- Meier DE, Bowman B. The changing landscape of palliative care. Am Soc Aging 2017; 41(1):74-80. [ Google Scholar]

- Sinnarajah A, Earp M, Biondo P, Piquette C, Vandale J, Tang PA. The PaCES (Palliative Care Early and Systematic) project: impact of individual components of a multi-faceted intervention on early referral to specialist palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40(28S):199. doi: 10.1200/JCD.2022.40.28_suppl.199 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Loffredo AJ, Chan GK, Wang DH, Goett R, Isaacs ED, Pearl R. United States best practice guidelines for primary palliative care in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2021; 78(5):658-69. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.05.021 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. 6th ed. London: Pearson; 2019.

- Gunaga S, Zygowiec J. Primary palliative care in the emergency department and acute care setting. Cancer Treat Res 2023; 187:115-35. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-29923-0_9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lynn J, Schall MW, Milne C, Nolan KM, Kabcenell A. Quality improvements in end-of-life care: insights from two collaboratives. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 2000; 26(5):254-67. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(00)26020-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Westermair AL, Buchman DZ, Levitt S, Perrar KM, Trachsel M. Palliative psychiatry in a narrow and in a broad sense: a concept clarification. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2022; 56(12):1535-41. doi: 10.1177/00048674221114784 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Coulon A, Bourmorck D, Steenebruggen F, Knoops L, De Brauwer I. Accuracy of the “surprise question” in predicting long-term mortality among older patients admitted to the emergency department: comparison between emergency physicians and nurses in a multicenter longitudinal study. Palliat Med Rep 2024; 5(1):387-95. doi: 10.1089/pmr.2024.0010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ansar A, Lewis V, McDonald CF, Liu C, Rahman A. Defining timeliness in care for patients with lung cancer: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open 2020; 10(11):e039660. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039660 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F, Wenk R, Ali Z, Bhatnaghar S. Redefining palliative care-a new consensus-based definition. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 60(4):754-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- van der Weegen K, Hoondert M, Timmermann M, van der Heide A. Ritualization as alternative approach to the spiritual dimension of palliative care: a concept analysis. J Relig Health 2019; 58(6):2036-46. doi: 10.1007/s10943-019-00792-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tuppal CP, C Reñosa MD, Ninobla MM, Ruiz MG, Loresco RC. Amo Ergo Sum—I love, therefore, I am–emotional synchrony: A Norris’ method of concept clarification. Nurse Media J Nurs 2019; 9(2):176-96. doi: 10.14710/nmjn.v0i0.23261 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CDThe MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36)IConceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30(6):473-83. [ Google Scholar]

- Kerr L, Macaskill A. Advanced Nurse Practitioners’ (Emergency) perceptions of their role, positionality and professional identity: A narrative inquiry. J Adv Nurs 2020; 76(5):1201-10. doi: 10.1111/jan.14314 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Abel J, Kellehear A, Mills J, Patel M. Access to palliative care reimagined. Future Healthc J 2021; 8(3):e699-702. doi: 10.7861/fhj.2021-0040 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]